Sinope ancient Kale excavations 2015: towards a new model of mobile fishing communities and incipient trade in the Black Sea

Introduction

The Sinop Regional Archaeological Project (SRAP) conducted its first season of excavation at Sinop Kale during July and August 2015, with major funding from the National Geographic Society (CRE 9318-13), the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-51768), British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, CSU Northridge, Queens College and Gonzaga University. Sinop (ancient Sinope) was one of the earliest Ionian Greek colonies in the Black Sea and the earliest colony on its Anatolian coast. The site of Sinop Kale is set directly overlooking the sea where a narrow sandy isthmus connects the mainland to a prominent basalt headland. The site, atop a 15m-high cliff above the shore, affords an unobstructed view of the coast in all directions. The site is ideally located for fishing and defensive purposes, and has little access to a terrestrial catchment more suited to a diversified agricultural economy. Fishing in this region is determined by the annual migrations of the major Black Sea fish species. These spawn in the shallow waters along the north coast and migrate in highly predictable cycles around the sea. The seasonal mobility patterns of these fish populations appears to have been a powerful determining factor that drove fishing communities to adopt mobile settlement strategies and stimulated incipient trade networks.

The primary goals for our 2015 field season were to clarify the Iron Age and early colonial phases of settlement investigated by SRAP in 2000 (Doonan 2007), and to establish the stratigraphic relationship of the defensive wall to early colonial and pre-colonial phases of the site. Ground-penetrating radar investigations of Sinop Kale carried out in December 2012 suggested that early strata should be accessible beneath a paved modern surface to the west of the city wall, so we concentrated efforts there in our initial season (Doonan et al. 2015).

SRAP had already conducted a scarp excavation of several exposed stone structures during the summer of 2000, and established that these belonged to the early to middle Iron Age (c. 1000–700 BC). The architecture was unlike local pre-colonial construction in the Sinop region and the handmade ceramics with horizontal bands of finger-impressed decoration were made of non-local pastes that showed the closest parallels to examples from the north and west coasts of the Black Sea. The structures resemble the dug-out and semi dug-out houses from the same region that are associated with the earliest phases of Ionian colonisation (c. 650–630 BC; Tsetskhladze 2004). A few sherds also showed parallels to the buff-burnished wares with faceted rims and handles of the Bafra plain 100km to the east (Doonan 2007). The site thus indicated great potential to shed light on pre-colonial interaction in the Black Sea and its impact on subsequent colonial economic and political systems.

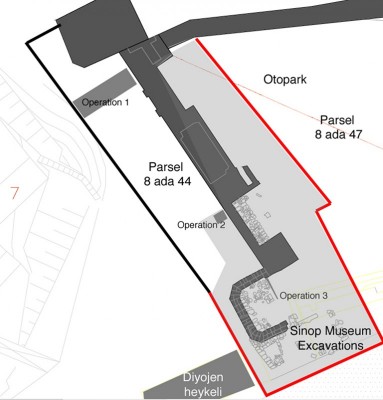

Our 2015 fieldwork was limited in terms of the areas available for excavation and in time. Three areas, or operations, were opened in a three-week season: the first was a 5 × 10m trench perpendicular to the line of the city wall; the second was a 2 × 2m trench against the wall extending from the edge of the excavations previously carried out by the Sinop Museum, and the third trench cut back a section protected under an Ottoman concrete cap in a tower. The most significant finds of the season include: the first evidence ever documented of Early Bronze Age settlement in the urban area of Sinop, including settlement debris and a dug-out stone structure; a rectangular house built of hewn stones associated with Archaic Ionian ceramics; documentation of an extensive early colonial settlement with handmade wares used together with Ionian Archaic (sixth century BC) and Athenian Classical (fifth- to fourth-centuries BC) ceramics; evidence for the relationship of the city wall to Archaic and Classical horizons; a late Hellenistic destruction episode possibly associated with the sack of the city by Lucullus in 70 BC; and a previously undocumented Byzantine curtain wall running parallel to the main, earlier curtain wall and approximately 5m to its west. The current report focuses on the results pertaining to the earliest phases.

Pre-colonial and early colonial phases

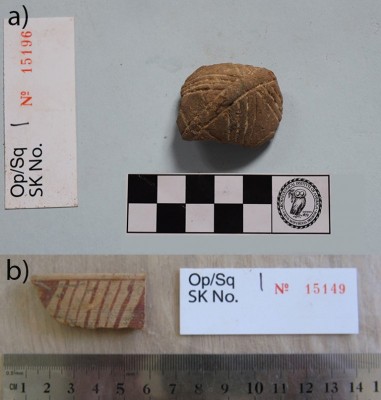

The Early Bronze Age ceramics (including an incised spindle whorl) demonstrate continuity in settlement as far back as the late third millennium BC. This is a period during which settlements on the Sinop promontory show broad connections around the Black Sea, in particular to Thracian and Bulgarian regions (Bauer 2006). The two stone-built structures are associated with ceramics from the north-west Black Sea and Ionia respectively.

The dug-out structure on the west side of operation 1 is constructed of unshaped beach cobbles associated with a series of ephemeral surfaces that can be identified by superimposed strata of flat-lying sherds. There was no evidence of compacted floor surfaces, leading to our provisional interpretation of this feature as a transient camp that was revisited repeatedly rather as than a house occupied for a more continuous period. The ceramic assemblage consists primarily of handmade wares, decorated with horizontal bands of finger-impressed designs. A bone fish-hook and fish bones were recovered from this structure, consistent with its interpretation as an intermittent fishing camp. Finds of terrestrial animal bones may suggest exchange between outside transient fishermen and indigenous communities. A limited number of Iron Age burnished buff-wares with faceted handles and rims suggest another connection with the Bafra plain, around 100km to the east. Our provisional working model is that these two houses and their associated ceramics indicate that Sinop was an early node in a mobile network in which people from various Black Sea coastal communities took advantage of seasonal fishing opportunities. It is probable that mutually beneficial relationships with inland communities were established as early as the Early Bronze Age (mid–late third millennium BC), and that this accounts for a limited spread of ceramics from as far away as the north and west coasts of the Black Sea. It seems clear that these early interactions became much more intensive during the early first millennium BC.

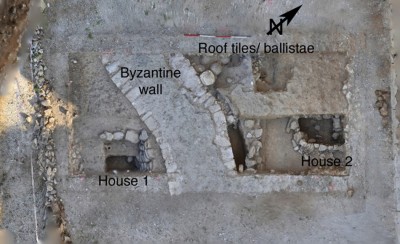

The stone house on the east side of operation 1 appears, on the basis of ceramic finds, to have been built during the Iron Age. This structure was constructed of hewn stones built in a roughly rectangular plan; it is unclear whether this structure was also semi-subterranean. Ionian painted wares associated with this structure are of a type undocumented at any other site in the SRAP survey area. Based on the ceramic finds and the form of the structure, we suggest that this house belongs to the early colonial foundation led by the great Ionian city of Miletus. It is unclear, however, whether it belongs to the earliest colonial phase, and subsequent excavations will aim to clarify this issue. A Byzantine wall defines a sharp break between the pre-colonial and the colonial contexts in the west and east parts of the trench respectively. This configuration appears to offer the remarkable opportunity to compare directly a range of environmental and cultural transitions between these two phases of the site.

Based on the smaller stratigraphic operations 2 and 3, it is clear that the early colonial settlement spread extensively to the south and probably to the east. Operations 2 and 3 documented local handmade wares together with Archaic (sixth-century BC) and Classical (fifth- to fourth-centuries BC) Ionian and Athenian ceramics. The city wall appears to have been built on top of an Archaic or Classical (sixth–fifth centuries BC) burial ground, and an early phase of the wall may date to the fourth or third century BC, considerably earlier than the usual assumption that the wall is to be dated to the period of the conquest of the site by Pharnakes I in the early second century BC. Our investigations of the stratigraphy of the wall are highly preliminary and will be clarified in upcoming seasons.

The first season of excavations at Sinop Kale has set the stage for highly significant new interpretations of early mobility, connectivity and incipient trade in the Black Sea. The model of mobile fishing communities interacting with local sedentary populations may represent a maritime extension of the ‘steppe and the sown’ model in Eurasia, and may have broader implications for the emergence of trade systems in the Mediterranean and other regions.

References

- BAUER, A.A. 2006. Between the steppes and the sown: prehistoric Sinop and inter-regional interaction along the Black Sea coast, in D.L. Peterson, L.M. Popova & A.T. Smith (ed.) Beyond the steppe and the sown: 227–46. Leiden: Brill.

- DOONAN, O. 2007. New evidence for the emergence of a maritime Black Sea economy, in V. Yanko-Hombach, A. Gilbert, N. Panin & P. Dolukhanov (ed.) The Black Sea flood question: changes in coastline, climate and human settlement: 697–710. Dordrecht: Springer.

- DOONAN, O., A. BAUER, A. CASSON, M. CONRAD, M. BESONEN, E. EVREN & K. DOMZALSKI. 2015. Sinop Regional Archaeological Project: report on the 2010–2012 field seasons, in S. Steadman & G. McMahan (ed.) The archaeology of Anatolia: current work: 298–327. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press.

- TSETKHLADZE, G.R. 2004. On the earliest Greek colonial architecture in the Pontus, in C. Tuplin (ed.) Pontus and the outside world. Colloquia Pontica 9: 225–78. Leiden: Brill.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Owen Doonan*

Program in Art History, California State University Northridge, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330-8300, USA (Email: owen.doonan@csun.edu) - Hüseyin Vural

Sinop Archaeological Museum, Okullar Caddesi 2, 57000 Sinop, Turkey - Andrew Goldman

History Department, Gonzaga University, 502 E. Boone Avenue, AD Box 035, Spokane, WA 99258-0035, USA (Email: goldman@gonzaga.edu) - Alexander Bauer

Department of Anthropology, Queens College, 65–30 Kissena Boulevard, Flushing, NY 11367, USA (Email: alexander.bauer@qu.cuny.edu) - E. Susan Sherratt

Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, Northgate House, West Street, Sheffield, S1 4ET, UK (Email: s.sherratt@sheffield.ac.uk) - Jane Rempel

Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, Northgate House, West Street, Sheffield, S1 4ET, UK (Email: j.rempel@sheffield.ac.uk) - Krzysztof Domzalski

Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Al. Solidarnosci 105, 00-140 Warsaw, Poland (Email: domzalkc@hotmail.com) - Anna Smokotina

Research Center of History and Archaeology of Crimea, Crimean Federal University, 4 Vernadsky Avenue, Simferopol, 295007, Republic of Crimea, Russian Federation (Email: asmokotina@mail.ru)

Cite this article

Cite this article