The formation of terraced landscapes in the Judean Highlands, Israel

Research framework

Terraces constitute a major technological innovation in the history of agriculture, transforming valleys and slopes into series of flat plots while reducing soil erosion and increasing infiltration. Their wide-scale distribution in numerous highland regions across the globe was not only a point of no return in human alteration of the environment (Arnáez et al. 2015), but also had far-reaching cultural implications with relation to the organisation of rural labour, economic decision-making and, possibly, carrying capacities and demographic trends. In the Mediterranean basin, terraces became one of the most defining features of the scenery, the result of prolonged formation processes (Bevan & Conolly 2011). Given that terraced landscapes are essentially palimpsests (Figure 1), identifying and dating initial terracing operations and later cycles of terrace construction and use are notoriously difficult, and most dating methods prevalent in past studies (Price & Nixon 2005) are now considered insufficient to overcome these challenges (Davidovich et al. 2012). The importance of reliable dating of terraces cannot be underestimated, as it holds the key for accurate reconstructions of landscape formation processes and their reciprocal relations with cultural trajectories in the Mediterranean highlands and elsewhere.

The present research project, ‘The formation of terraced landscapes in the Judean Highlands’, is a comprehensive terrace-dating venture involving the use of optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating of terrace infills in combination with careful analyses of related geomorphological and archaeological records. The research traces the socio-economic and historical contexts in which terraces were initially spread over the rural periphery of Jerusalem, a thriving political, economic and religious centre for four millennia, as well as later chapters of terrace construction. It seeks to test current paradigms concerning the cultural transformation of the Judean landscape, mainly in terms of the age of the terrace phenomenon—variously suggested to date to different Bronze and Iron Age phases—and the assumed correlation between population increase and extensive terracing (Gibson 2001). This project builds on two previous studies, in which the research methodology was formalised and the reliability of OSL ages was established (Davidovich et al. 2012; Avni et al. 2013). The current project commenced in October 2013 with support from the Israel Science Foundation.

Methods

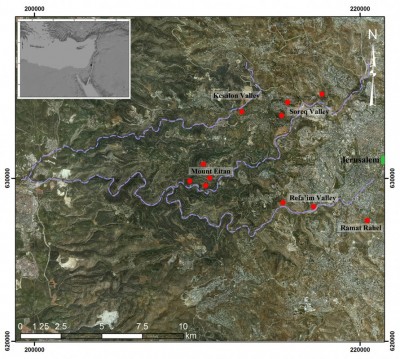

The Jerusalem Highlands, typified by moderate Mediterranean climate and natural maquis vegetation, are extensively terraced, with estimated land cover of nearly 60 per cent (Ron 1966) (Figure 2). The region is bisected by three east–west flowing ephemeral streams (Kesalon, Soreq and Refa’im, all part of the Soreq catchment), each have numerous small tributaries (Figure 3). The upper reaches of the main valleys are relatively wide, containing quasi-flat areas with deep soils; according to previous archaeological explorations, these were the primary locations of rural settlements in Jerusalem’s periphery. Most of the region, however, is characterised by narrow riverbeds and moderately steep slopes. In order to sample the diversity of agricultural landscapes, four study areas were defined, three within the main valleys and one (Mount Eitan) on an isolated hilly spur in the centre of the region (Figure 3).

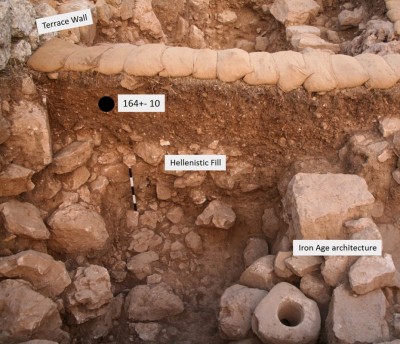

In each study area, selected terrace systems, ranging from well-preserved standing terraces to barely visible deteriorated remnants, are documented in detail, including morphometric parameters, building techniques and the typology of walls and stones used. Spatial relations between terraces and other cultural features are further analysed. Multiple test pits are manually excavated in each system, and sediment profiles are stratigraphically scrutinised and sampled for soil characterisation and OSL dating (Figures 4 & 5). Pottery from excavated test pits is collected and analysed by comparison with surface surveys of the terraced systems and past archaeological explorations of settlement sites in the study areas. Historical data referring to the use of terraces in the recent past, such as maps and tax censuses from the Ottoman and British Mandate periods, are gathered and compared with OSL results and material culture analysis.

Implications

The main premise of the research is the dating of a large (~150) number of OSL samples, a feat never attained before in the study of agricultural landscapes. The large dataset will allow a detailed analysis of the formation processes of the OSL record and related soils, and, using several statistical tools, and for the main periods of terrace construction and use in the region to be pinpointed. The emerging OSL age patterns, investigated vis-à-vis regional settlement patterns evolving from archaeological surveys and historical records, enable for the first time a complete assessment of the transformation of the Judean Highlands from a natural ‘wildscape’ to the cultural landscape they form today. The research will enrich our knowledge of dry farming landscape formation across the Mediterranean, and, together with new results from other regional studies, will hopefully contribute to the inter-regional discourse on the social and historical significance of terraces at this cradle of western civilisations.

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by an Israel Science Foundation grant (Grant 0606714492) awarded to Yuval Gadot and Naomi Porat. The Israel Antiquities Authority, National Parks Authority and Jewish National Fund approved and supported fieldwork.

References

- ARNÁEZ, J., N. LANA-RENAULT, T. LASANTA, P. RUIZ-FLAŇO & J. CASTROVIEJO. 2015. Effects of farming terraces on hydrological and geomorphological processes: a review. Catena 128: 122–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2015.01.021

- AVNI, G., N. PORAT & Y. AVNI. 2013. Byzantine–Early Islamic agricultural systems in the Negev Highlands: stages of development as interpreted through OSL dating. Journal of Field Archaeology 38: 332–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/0093469013Z.00000000052

- BEVAN, A. & J. CONOLLY. 2011. Terraced fields and Mediterranean landscape structure: an analytical case study from Antikythera, Greece. Ecological Modelling 222: 1303–314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.12.016

- DAVIDOVICH, U., N. PORAT, Y. GADOT, Y. AVNI & O. LIPSCHITS. 2012. Archaeological investigations and OSL dating of terraces at Ramat Rahel, Israel. Journal of Field Archaeology 37: 192–208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/0093469012Z.00000000019

- GIBSON, S. 2001. Agricultural terraces and settlement expansion in the highlands of Early Iron Age Palestine: is there a correlation between the two?, in A. Mazar (ed.) Studies in the archaeology of the Iron Age in Israel and Jordan: 113–46. Sheffield: Sheffield University Press.

- PRICE, S. & L. NIXON. 2005. Ancient agricultural terraces: evidence from texts and archaeological survey. American Journal of Archaeology 109: 665–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.3764/aja.109.4.665

- RON, Z. 1966. Agricultural terraces in the Judean Mountains. Israel Exploration Journal 16: 33–49.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Yuval Gadot*

The Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, Tel Aviv University, P.O.B. 39040, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel (Email: ygadot@gmail.com) - Uri Davidovich

McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3ER, UK (Email: uri.davidovich@mail.huji.ac.il) - Gideon Avni

Israel Antiquities Authority, P.O.B. 586, Jerusalem 9100402, Israel (Email: gideon@israntique.org.il) - Yoav Avni

Geological Survey of Israel, 30 Malkhe Israel Street, Jerusalem 9550161, Israel (Email: yavni@gsi.gov.il) - Naomi Porat

Geological Survey of Israel, 30 Malkhe Israel Street, Jerusalem 9550161, Israel (Email: naomi.porat@gsi.gov.il)

Cite this article

Cite this article