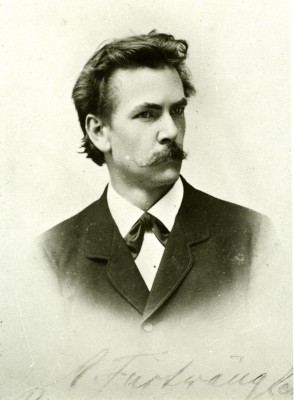

Adolf Furtwängler (1853–1907): ‘The Linnaeus of classical archaeology’

Although Adolf Furtwängler (1853–1907) was one of the most prolific and influential classical archaeologists of his generation, his wide-ranging contribution to the discipline is little discussed in its modern histories. There are several possible reasons for this: Furtwängler’s early pioneering fieldwork in Greece during the 1870s formed part of high-profile projects that he did not direct himself; he then turned to the study of previously collected and often well-known artworks in museums and private collections—important work, but rarely acknowledged in such disciplinary histories; and finally, he did not introduce any revolutionary theories or innovative methods. Nonetheless, the results of his rigorously systematic approach to great masses of objects have made a profound and lasting impact in several areas of the discipline.

Born to middle-class parents, Furtwängler grew up with two sisters and a brother in Catholic Freiburg. He attended the local gymnasium, directed by his own father, but was formally excused in his final year to finish his studies from home, and later expressed dislike for schools and other institutions such as the military. Yet he did well, and went on to study philosophy and philology at Freiburg and Leipzig before turning to archaeology at Munich, where his dissertation on Eros in Greek vase-painting (Furtwängler 1874) was supervised by Heinrich Brunn (1822–1894), a pioneer in the study of ancient art who had spent two decades in Rome acquiring extensive first-hand knowledge, of sculpture in particular.

Furtwängler graduated in 1874 and spent the years 1876–1878 in Italy and Greece supported by a travel grant from the German Archaeological Institute. After a year in Rome, where he focused on studying sculpture in the great public and private collections, he was hired by the excavation team at Olympia. Before the digging season started, he and Georg Loeschcke (1852–1915) were set to work in the Athens Polytechnikon, where they brought order to the unsorted pottery sherds from Schliemann’s Mycenae excavations. Their meticulous studies of shapes and designs (Furtwängler & Loeschcke 1879, 1886) showed the great potential of this previously neglected archaeological evidence and laid the foundations for future research. Equally significant was Furtwängler’s work at Olympia, where he carefully documented bronzes and small finds, linking them to stratigraphical data and developing useful typologies and a chronological framework. His volume in the Olympia series (Furtwängler 1890) remained a long-standing model for such publications.

On his return to Germany, Furtwängler habilitated in Bonn under Reinhard Kekulé (1839–1911) and was then hired by the expanding Berlin Museums as a curatorial assistant, first to Alexander Conze (1831–1914) in the sculpture department, then to Ernst Curtius (1814–1896) in the Antiquarium. The experience gained in Italy and Greece had prepared him well for this kind of work, and his 14 years in Berlin (1880–1894) turned out to be exceptionally productive. Equipped with a remarkable visual memory and a talent for structuring great masses of materials (which earned him the epithet “Linnaeus of Archaeology”; Riezler 1965: 9), Furtwängler set to work on the collections and produced impressive catalogues of the museum’s 4000 vases (Furtwängler 1885) and 12 000 engraved gems (Furtwängler 1896). He also published the Sabouroff collection (Furtwängler 1883/1887), finished his manuscripts on Mycenaean pottery and bronzes from Olympia, wrote numerous encyclopedia entries, articles and reviews, as well as teaching art history at the Königin-Luise-Stiftung and archaeology at the university, where he was made professor extraordinarius in 1884, although he was never offered a chair. His work also included extensive travelling to major museums, private collections and auction houses. Soon he had acquired an extraordinary command of a wide spectrum of materials and become exceptionally well connected in the international world of curators, collectors and dealers. These contacts, expertly cultivated for mutual benefit, constituted Furtwängler’s primary powerbase, especially after he left Berlin for Munich.

While in Berlin, Furtwängler married the artist Adelheid Wendt (1863–1944), with whom he had four children. Despite being very productive, these happy family years were clouded by friction at work. Furtwängler had always suffered from a bad temper and paranoid tendencies, which resulted in strained relations with his superiors and colleagues, with whom he interacted in a tactless and often aggressive manner. Conze found him difficult to work with and soon had him reassigned to the more sympathetic Curtius in the Antiquarium. The situation worsened after 1889 with the appointment of Kekulé as director of the sculpture department and later to the university chair in archaeology. Furtwängler, who saw himself as the best candidate for both positions and had already declined offers from lesser universities, was bitterly disappointed. These negative professional experiences and personality traits interfered with his work and are also reflected in his publications, where references to his colleagues’ work are often unreasonably harsh and sometimes border on personal attacks. The controversial Meisterwerke volume (Furtwängler 1893), Furtwängler’s last work from the Berlin years and a milestone in the field of ‘Kopienkritik’, is one example. Still, even those who disliked and dreaded Furtwängler as a person generally acknowledged the quality of his scholarship.

Although a mediocre and often ill-prepared speaker, Furtwängler’s otherwise well-informed lectures always drew large, enthusiastic crowds. He was a pioneer in the use of lantern slides as a teaching tool and took full advantage of photography in his own research and lavishly illustrated publications. His magnum opus, the three-volume history of ancient gem-engraving (Furtwängler 1900), contained high-quality reproductions of over 3600 items. In order to understand his material better, Furtwängler found that he often had to start from scratch and examine afresh the whole corpus of artefacts. The primacy of original objects and the importance of his own empirical work were repeatedly stressed in his publications, often at the expense of previous scholarship, on which Furtwängler drew considerably more than he acknowledged. Working at the height of positivism and influenced by Darwin and Haeckel—whose work he knew well—Furtwängler’s Winckelmannian belief in the absolute normativity of Greek classical art nevertheless remained unshakable throughout his career.

In 1894, on recommendation from both Conze and Kekulé who wanted him out of Berlin, Furtwängler was at last called to a prestigious chair, succeeding his teacher Brunn in Munich. He was also appointed director of four important Bavarian collections, including the Glyptothek, which housed the pediment sculptures from the temple of Aphaia on Aegina. Dissatisfied with Thorvaldsen’s reconstruction of these sculptures and to understand their context better, Furtwängler embarked on new and successful excavations of the sanctuary in 1901. During the 1907 campaign, he contracted dysentery and was taken to the Evangelismos hospital in Athens, where he died a few days later on 10 October. Adolf Furtwängler was honoured with a Greek state funeral and is buried in Athens’ First Cemetery.

The present author has recently completed a larger study of Adolf Furtwängler’s scholarly contribution to classical archaeology, “The Linnaeus of classical archaeology”: Adolf Furtwängler and the great systematization of antiquity (Hansson n.d.)

References

- FURTWÄNGLER, A. 1874. Eros in der Vasenmalerei. München: Ackermann.

– 1883/1887. Die Sammlung Sabouroff: Kunstdenkmäler aus Griechenland. Berlin: Asher & Company.

– 1885. Beschreibung der Vasensammlung im Antiquarium, Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Berlin: W. Spemann.

– 1890. Olympia: die Ergebnisse der von dem deutschen Reich veranstalteten Ausgrabung, 4, Die Bronzen und übrigen kleineren Funde von Olympia. Berlin: Asher & Co.

– 1893. Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik. Leipzig: Giesecke & Devrient.

– 1896. Beschreibung der Geschnittenen Steine im Antiquarium. Berlin: W. Spemann.

– 1900. Die antiken Gemmen: Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst im klassischen Altertum. Berlin & Leipzig: Giesecke & Devrient. - FURTWÄNGLER, A. & G. LOESCHCKE. 1879. Mykenische Thongefässe. Berlin: A. Asher.

– 1886. Mykenische Vasen: vorhellenistische Tongefässe aus dem Gebiet des Mittelmeeres. Berlin: A. Asher. - HANSSON, U.R. n.d. “The Linnaeus of classical archaeology”: Adolf Furtwängler and the great systematization of antiquity. Available at: http://www.isvroma.it/public/New/index.php?option=com_content&view=artic... (accessed 28 October 2014).

- RIEZLER, W. 1965. ‘Adolf Furtwängler zum Gedächtnis’, in A. Greifenhagen (ed.) Briefe aus dem Bonner Privatdozentenjahr 1879/80 und der Zeit seiner Tätigkeit an den Berliner Museen 1880–1894: 8–10. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Author

- Ulf R. Hansson

Department of Classics, University of Texas at Austin, 2210 Speedway Mailcode C3400, Austin TX 78712-1738, USA (Email: ulf.hansson@austin.utexas.edu)

Cite this article

Cite this article