Unusual funeral practices and violence in Early Neolithic Central Europe: new discoveries at the Mulhouse-Est Linearbandkeramik

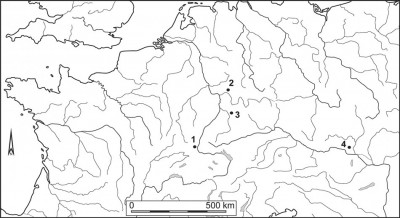

Following earlier excavations from 1964–1972 at the Mulhouse-Est Early Neolithic cemetery in the commune of Illzach (Haut-Rhin, France) (Schweitzer & Schweitzer 1977), a new season of work was carried out during August 2014 (Figure 1). Two new burials were added to the 22 previously excavated and dated to the middle phase of the Linearbandkeramik culture (LBK), c. 5100 BC, making Mulhouse-Est one of the oldest cemeteries in the western area of the LBK (Jeunesse 1997). The dead were buried according to the funerary rite of the Early Danubian Neolithic: flexed body placed on its left side with the head to the north-east, sprinkled with red ochre and accompanied by relatively abundant and diverse grave goods. The most spectacular assemblage found during the earlier excavations comes from Grave 14, in which a woman had been buried with no fewer than 1056 beads, including several hundred made of seashell, and a Spondylus bracelet. The results of this earlier work have been the subject of anthropological study (Gerhardt & Gerhardt-Pfannenstiel 1985) and, more recently, palaeo-biological analyses as part of the project ‘Diversity in LBK Lifeways’ (Bickle & Whittle 2012).

The two burials excavated in 2014 complement existing knowledge of the site with two completely new configurations. The first burial displays the usual characteristics—orientation, abundant use of ochre, grave form; the skeletal remains, however, are unusually fragmentary, comprising approximately 60 small pieces mainly from the ribs, as well as small, complete bones from the hands and feet. Except for a few small fragments, the skull, the long bones and the pelvis are missing. The presence of grave goods (a fragment of Spondylus ornament and a nodule of iron ore) and of a thick layer of ochre-stained sand suggest that the pit originally contained a complete body, which was disturbed after the decomposition of the flesh, and the remaining bones were then interred and carefully covered with red ochre. Detailed analysis of the remains is ongoing and will investigate this working hypothesis. The extent and homogeneity of the red ochre layer provides, at least, good reason to reject the suggestion of post-LBK disturbance. A few LBK burials with evidence for small-scale reorganisation (Jeunesse 2003), and symbolic graves without any skeletal remains at all, are known from elsewhere, but the extensive removal of bone now attested at Mulhouse-Est is unique in the Central European Early Neolithic.

The second grave excavated in 2014 contained the very well-preserved remains of a teenage male who died between 15 and 20 years of age and was buried in a flexed position with his head to the north-north-east. The particular interest of this burial lies, on the one hand, in the assemblage of grave goods and, on the other, in the existence of very strong evidence for the man’s violent death. The assemblage comprises a fire-lighting kit (a flint striker associated with a piece of iron ore), a Spondylus ring, a decorated pot, an adze blade and a perforated antler axe (Figures 2 & 3). The latter is 28cm in length and was positioned leaning in an upward position against the right side of the skull. It belongs to a type seldom found in general LBK contexts and which exists only in the Upper Rhine basin (Alsace and Neckar) throughout the LBK II and III phases; the only other known example from a funerary context was recently discovered in southern Alsace (Vergnaud & Maurer 2014). In addition to the notable grave goods, our attention was immediately caught by an arrowhead discovered inside the rib cage (Figure 4). Closer examination has shown that its extremity was broken and that the 7mm-long point fragment was lodged between two ribs, at the right shoulder level, and embedded in a concretion. The presence of a notch on the clavicle leaves few doubts concerning the interpretation of these facts: the individual was hit by an arrow that penetrated his body under the clavicle, incidentally damaging it; the arrowhead broke on impact. The shot might not necessarily have been lethal, yet the lack of evidence for healing suggests that the individual’s death quickly followed, quite probably in relation to the general violent event associated with the arrow shot. Signs of violence are quite abundant during the LBK, for which at least three massacre sites are known, each resulting in the deaths of dozens of individuals: Talheim (Wahl & Trautmann 2012) and Kilianstädten (Meyer et al. 2013) in Germany, and Asparn-Schletz in Austria (Teschler-Nicola 2012). However, the wounds of those found at these massacre sites are almost always caused either by a blunt instrument or by the cutting edge of an adze. Our ongoing studies will attempt to reconstruct the precise trajectory of the arrow and to study the geological and cultural origin of its arrowhead, which belongs to a type still unknown in the Alsatian LBK.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Emmanuelle Thauvin-Boulestin for translating this article.

References

- BICKLE, P. & A. WHITTLE (ed.) 2013. The first farmers of central Europe. Diversity in LBK lifeways. Oxford: Oxbow.

- GERHARDT, K. & D. GERHARDT-PFANNENSTIEL. 1985. Schädel und Skelette der Linearbandkeramik von Mulhouse-Est (Rixheim) im Elsass. Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica 16–17: 55–90.

- JEUNESSE, C.H. 1997. Pratiques funéraires au Néolithique ancien. Sépultures et nécropoles danubiennes, 5500–4900 av. J.C. Paris: Errance.

– 2003. Les pratiques funéraires du Néolithique ancien danubien et l'identité rubanée: découvertes récentes, nouvelles tendances de la recherche, in P. Chambon & J. Leclerc (ed.) Les pratiques funéraires néolithiques avant 3500 av. J.C. en France et dans les régions limitrophes (Mémoires de la Société Préhistorique Française 33): 19–32. Paris: Société Préhistorique Française. - MEYER, C., C. LOHR, H.-C. STRIEN, D. GRONENBORN & K. ALT. 2013. Interpretationsansätze zu irregulären“ Bestattungen während der linearbandkeramischen Kultur: Gräber en masse und Massengräber, in N. Müller-Scheessel (ed.) Irreguläre Bestattungen in der Urgeschichte: Norm, Ritual, Strafe…? Akten der Internationalen Tagung in Frankfurt a. M. vom 3 bis 5 Februar 2012: 111–22. Bonn: Römisch-Germanische Kommission des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts & Habelt.

- SCHWEITZER R. & J. SCHWEITZER. 1977. La nécropole danubienne de Mulhouse-Est. Bulletin du Musée Historique de Mulhouse 84: 11–63.

- TESCHLER-NICOLA, M. 2012. The Early Neolithic site Asparn/Schletz (Lower Austria): anthropological evidence of interpersonal violence, in R. Schulting & L. Fibiger (ed.) Sticks, stones and broken bones: Neolithic violence in a European perspective: 101–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- VERGNAUD, L. & D. MAURER. 2014. Les sépultures rubanées du site de Wittenheim ‘Le moulin’ (Haut-Rhin), in P. Lefranc, A. Denaire & C. Jeunesse. (ed.) Données récentes sur les pratiques funéraires néolithiques de la Plaine du Rhin supérieur (du Rubané au Campaniforme). Actes de la table ronde de Strasbourg, 1er juin 2011 (British Archaeological Reports international series 2633): 59–66. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- WAHL, J. & I. TRAUTMANN. 2012. The neolithic massacre at Talheim: a pivotal find in conflict archaeology, in R. Schulting & L. Fibiger (ed.) Sticks, stones and broken bones: Neolithic violence in a European perspective: 77–100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Christian Jeunesse*

Department of Archaeology, Université de Strasbourg & CNRS UMR 7044, MISHA, 5 allée du Général Rouvillois, Strasbourg 67000, France (Email: jeunessechr@free.fr) - Hélène Barrand-Emam

Antéa-Archéologie, 11 rue de Zurich, Habsheim, 68440, France & CNRS UMR 7044, MISHA, 5 allée du Général Rouvillois, Strasbourg 67000, France (Email: helenebarrand@hotmail.com) - Anthony Denaire

Antéa-Archéologie, 11 rue de Zurich, Habsheim, 68440, France & CNRS UMR 7044, MISHA, 5 allée du Général Rouvillois, Strasbourg 67000, France (Email: denaire@neuf.fr) - Fanny Chenal

Antéa-Archéologie, 11 rue de Zurich, Habsheim, 68440, France (Email: fanny_chenal@hotmail.com)

Cite this article

Cite this article