Architecture, rock art and the settlement structure in the Castle Rock Community, Mesa Verde region, Colorado

The Sand Canyon-Castle Rock Community Archaeological Project was initiated in 2011 in the central Mesa Verde region of south-western Colorado, USA (Figure 1). The project focuses on the study of settlement structure and socio-cultural changes in ancient Pueblo culture during the thirteenth century AD, also known as the Late Pueblo III period. The project is being conducted by the Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland.

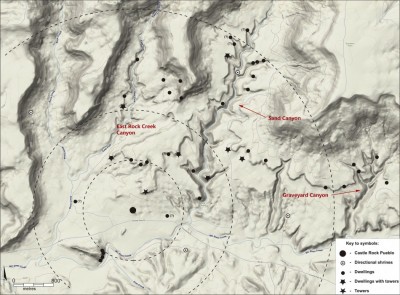

The research focuses on the Lower Sand Canyon area, specifically: Sand Canyon, East Rock Creek Canyon and Graveyard Canyon (Figures 2–4). This area forms part of the Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, a legally protected area administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). These canyons contain the remains of around 40 small sites, including habitations, limited activity sites and a large community centre—Castle Rock Pueblo—which probably functioned as a focus for allied sites during the thirteenth century AD. The Castle Rock Community was one of around 60 in the central Mesa Verde region at that time.

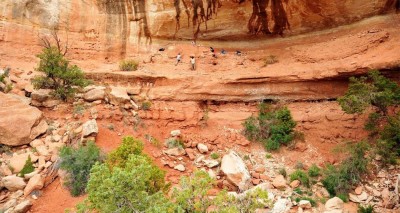

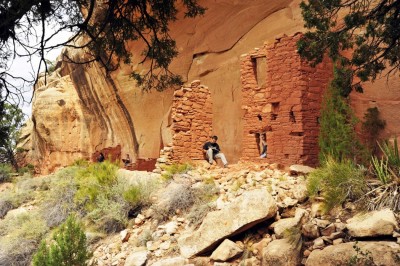

The thirteenth century AD was a period of great change in the Pueblo world of the Mesa Verde region. Settlement locations shifted from the mesa tops and uplands to canyon rims and cliff alcoves, and to other difficult-to-access places (Figure 2). Some of these settlements became large and well planned. Many types of public and defensive architecture—including plazas, great kivas, towers and stone enclosing walls—were also constructed during this period. This was a time of regional population peak, development in architecture and settlement systems and then, at the end of the thirteenth century AD, of depopulation and migration. The reasons for this migration are still not fully understood but may include environmental and climatic change, as well as increasing violence and conflict. The most probable destinations for Pueblo migrants include the northern and central parts of Arizona and New Mexico, where their descendants live today.

During the project’s five seasons (2011–2015), some 30 of the 40 small Pueblo sites known in the three canyons have been investigated using non-invasive techniques. Surveys included detailed documentation of extant architecture, with drawings, photography, photogrammetry and laser scanning (Figure 5). Geophysical survey, mainly electrical resistivity and magnetometry, was also conducted at several sites.

Of the community’s 40 sites, some 28 are located in difficult-to-access cliff alcoves and associated talus slopes. Most sites face south, south-east and south-west, directly towards the highest point in the area, Sleeping Ute Mountain, which rises approximately 3000m above sea level. Small sites usually comprise from three or four rooms to more than ten—the exact number can be difficult to establish because not all of the architecture survives or is visible on the surface. In this regard, the results of our initial geophysical research are very promising, showing that settlements were not limited to the interiors of cliff alcoves but also included a large number of buildings extending beyond. These results contribute to an understanding of the demography—both of individual sites and of the wider community—and they already suggest a much higher population density than we previously thought. At least two possible agricultural fields have also been identified using geophysics.

The precise mapping of settlements also facilitates an evaluation of their intervisibility and the potential for communication between settlements and stone towers in order to warn of an enemy’s approach or to call for ceremonies. At least eight sites in the Castle Rock Community contained one or more towers. Some free-standing towers in the lower portion of the Sand Canyon locality are very close to habitation sites; the distances range from 30–40m to as far as 100–120m . We hypothesise that the primary function of these towers was communication or observation, as most are intervisible with nearby sites; a secondary function might have been defence. Among the sites investigated, six clusters of four or more sites were either close to each other, or within visual contact. The boundary of the Castle Rock Community was probably marked by four shrines (stone circles). These are located roughly to the north, west, south and east of Castle Rock Pueblo.

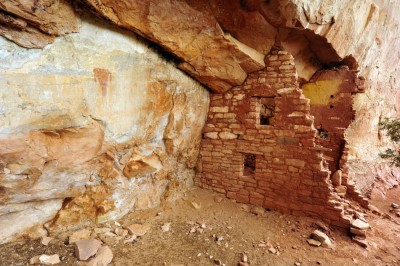

The rock art discovered and documented by our project includes paintings and petroglyphs; for example, a trapezoidal anthropomorphic figure at the Vision House site, and human figures with triangular bodies painted red and white at The Gallery site (Figures 6 & 7). These anthropomorphic figures probably date to the third–fifth centuries AD, much earlier than the main thirteenth-century occupation of nearby sites. At other sites, we documented more examples of petroglyphs, including spirals, zigzag lines and bird tracks. There are also murals at two sites documented by our project that include snakes (symbols of fertility), birds (probably turkeys) and dots painted in white on brown/red plaster. Modern graffiti, such as initials and names, is also present. Following the success of our initial seasons, we extended the documentation of rock art sites to an area located approximately 20km north-west of our core study region in 2013. The petroglyphs from these sites mostly depict geometric motifs, clan symbols (the bear paw appears most often), anthropomorhic figures (probably shamans) and extended scenes that include fighting and also the hunting of deer and bison (Figure 7).

The results of the project demonstrate that Pueblo settlements changed in both location and form during the thirteenth century AD; although physically difficult to access, many sites were intervisible with each other or with towers. There are also examples of connection between the architecture, shrines, site locations and layouts with the surrounding landscape and probably with the religious practices. Cliff-alcove sites appear to have been more extensive than previously thought, suggesting a higher population and adding to the debate about the causes of regional depopulation at the end of the thirteenth century.

Acknowledgements

The photographs are courtesy of Robert Słaboński (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University, 11, Gołębia Street, 31-007 Kraków, Poland; rslabonski [at] interia.pl). I am very thankful to Vince McMillan, from the Anasazi Heritage Center, BLM in Dolores, Colorado, and Dan Haas, state archaeologist, BLM in Lakewood, Colorado, for their invaluable help during the research. I would also like to express my gratitude to Mark D. Varien, Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Cortez, Colorado, for his help before and during the several seasons of the project. Our research in the USA was made possible by the financial support of numerous institutions to which I am very grateful, especially the Institute of Archaeology and the Faculty of History of Jagiellonian University in Krakow, the US Consulate General in Krakow, National Science Center, Poland, and the US Bureau of Land Management.

Author

* Author for correspondence.

- Radosław Palonka*

Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University, Golebia 11 Street, 31-007 Krakow, Poland (Email: radek.palonka@uj.edu.pl)

Cite this article

Cite this article