Palaeolithic research at Mochlos, Crete: new evidence for Pleistocene maritime activity in the Aegean

To reach Europe, archaic hominins followed multiple pathways, including a terrestrial route through south-west Asia (Carbonell et al. 2008), and perhaps across the Strait of Gibraltar to Iberia in the west (Rolland 2013). The Aegean has been proposed as another possible gateway to south-eastern Europe, both by land and by sea (Tourloukis & Karkanas 2012; Broodbank 2013: 82–108). But did archaic hominins use boats to cross the open sea with islands as possible way points (Simmons 2014: 203–12; Runnels in press)? During a geological study of a Quaternary alluvial fan sequence at Mochlos, Crete, the chance discovery of isolated artefacts of Lower and/or Middle Palaeolithic type may throw light on this question (Figure 1).

The as-yet-undated fan sequence extends 4km along the coast east of the modern village of Mochlos and reaches c. 600m inland. It was created during the Quaternary by large magnitude episodic sedimentation events within local watersheds through extensive erosion of upland mountain hinterlands to the south that produced vast volumes of boulders, cobbles and coarse-grained sediments, paving valley floors and accumulating in alluvial fans. These probably climate-forced, high-volume flows are interrupted periodically by extensive overbank deposits of finer-grained clastic sediments, formed perhaps during periods of climate stability. Fan development may have occurred during climate pulses, with intervening periods of stability that allowed vegetation growth and soil development. The fans graded out at times of glacial sea-level lowstands to a now-submerged shoreline several kilometres offshore. Today they terminate at the shoreline where steep scarps are being created by wave action. Two fans dominate the sequence. Mavroseli is the largest drainage watershed and the principal contributor to the fan sequence, augmented by a smaller fan in the Loutres drainage area.

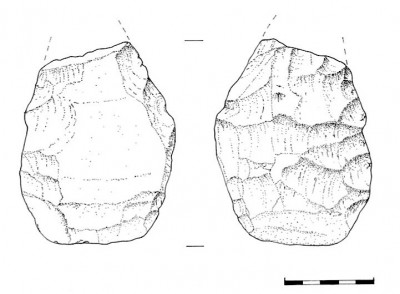

The Mavroseli fan is 2km east of Mochlos and is primarily depositional. Cut banks c. 15m deep expose a stratigraphic sequence of layers, each 2–3m thick, of cobbles and boulders created by outwash interbedded with finer-grained deposits that formed during periods of stability. In a stratigraphic section c. 10m deep and 300m inland (Figure 2), an amygdaloid/ovate biface (handaxe) (Figures 3 & 4) and a bifacial core or protobiface were observed in situ at a depth of c. 9m. The artefacts, 100–120mm in length, were fashioned from milky vein quartz by direct hard hammer percussion and were the only quartz clasts in the section. Their angular shapes suggest minimal transport before deposition.

The fan at Loutres, 1km east of Mochlos, has a stratigraphic section c. 5–7m thick exposed at the present shoreline, with a different depositional history than Mavroseli. At its base is a palaeochannel filled with cemented conglomerate. Above the palaeochannel is a Bt horizon of a palaeosol c. 3m thick with discontinuous stringers of gravel interrupted by small stream channels filled with debris flow materials. This palaeosol indicates a period of fan stability that permitted pedogenesis. Rhizolith fossils penetrating the palaeosol preserve root moulds of surface vegetation. This palaeosol exhibits a level of pedogenic maturity similar to palaeosols on the south-western coast of Crete at Plakias, which have been dated by OSL and pedogenic maturity to c. 114 ka (Strasser et al. 2011; Runnels in press). A stream subsequently incised this palaeosol, and in turn was filled with cobbles and boulders forming an overbank deposit, c. 0.5m thick, capping the lower palaeosol and truncating the rhizoliths. About 3m below the overbank deposit, large (>100mm) angular quartz flakes, a small (100mm) sub-triangular biface and a cleaver on a flake (110mm) were observed within the palaeosol (Figures 5 & 6). Above the overbank deposit another palaeosol c. 1–2m thick has mostly eroded away, but Palaeolithic artefacts, presumably derived from this palaeosol, including a possibly Middle Palaeolithic preferential flake core (85mm) of Levallois type (Figure 6), occur in a lag deposit on top of the overbank deposit.

The Lower and/or Middle Palaeolithic artefacts in the Quaternary alluvial fan sequence on the north-eastern coast of Crete at Mochlos, as well as Lower Palaeolithic artefacts from south-western Crete (e.g. Strasser et al. 2010, 2011), suggest maritime activity by archaic hominins, because Crete has been an island since the termination of the Messinian Salinity Crisis c. 5.33 ma, and it is likely that throughout the Pleistocene intentional open-sea travel was necessary to reach the island.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Institute for Aegean Prehistory and was a consequence of geological research permitted by the Institute for Geological and Mining Research in Athens.

References

- BROODBANK, C. 2013. The making of the Middle Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- CARBONELL, E., M. MOSQUERA, X.P. RODRÍGUEZ, J.M. BERMÚDEZ DE CASTRO, F. BURJACHS, J. ROSELL, R. SALA & J. VALLVERDÚ. 2008. Eurasian gates: the earliest human dispersals. Journal of Anthropological Research 64: 195–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/jar.0521004.0064.202

- ROLLAND, N. 2013. The early Pleistocene human dispersals in the circum-Mediterranean basin and initial peopling of Europe: single or multiple pathways? Quaternary International 316: 59–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2013.06.028

- RUNNELS, C.N. In press. Early Palaeolithic on the Greek islands? Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 27.

- SIMMONS, A.H. 2014. Stone Age sailors: Paleolithic seafaring in the Mediterranean. Walnut Creek (CA): Left Coast.

- STRASSER, T.F., E. PANAGOPOULOU, C.N. RUNNELS, P.M. MURRAY, N. THOMPSON, P. KARKANAS, F.W. MCCOY & K.W. WEGMANN. 2010. Stone age seafaring in the Mediterranean: evidence from the Plakias region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic habitation of Crete. Hesperia 79: 145–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.2972/hesp.79.2.145

- STRASSER, T.F., C.N. RUNNELS, K. WEGMANN, E. PANAGOPOULOU, F.W. MCCOY, C. DIGREGORIO, P. KARKANAS & N. THOMPSON. 2011. Dating Palaeolithic sites in southwestern Crete, Greece. Journal of Quaternary Science 26: 553–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1482

- TOURLOUKIS, V. & P. KARKANAS. 2012. The Middle Pleistocene archaeological record of Greece and the role of the Aegean in hominin dispersals: new data and interpretations. Quaternary Science Reviews 43: 1–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.04.004

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Curtis Runnels*

Department of Archaeology, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215, USA (Email: runnels@bu.edu) - Floyd McCoy

Department of Natural Sciences, University of Hawaii, 45-720 Kea’ahala Road, Kaneohe, HI 96744, USA - Robert Bauslaugh

Division of Humanities, Brevard College, 1 Brevard College Drive, Brevard, NC 28712, USA - Priscilla Murray

Department of Archaeology, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215, USA

Cite this article

Cite this article