EBERHARD SAUER 2003

The archaeology of religious hatred in the Roman and early Medieval world

Stroud & Charleston (SC): Tempus

|

|

|

Review by

W.H.C. FREND

Little Wilbraham, Cambridgeshire,UK

Antiquity 78 no. 300 June 2004

|

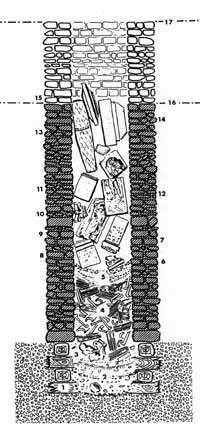

The destruction of pagan shrines and monuments in the reign of Theodosius I (379- 95), not least in Syria under the governorship of Cynegius, is well known. At this period, monks are described by Libanius as 'clothed in black and with the appetites of elephants', making 'illegal attacks on temples and destroying them completely with their images, with stones and iron implements' (Oratio 30 Pro templis 8). Sauer provides archaeological evidence for this with his scholarly and well researched study of the hatred felt by the perpetrators for all forms of paganism and its artwork. He concentrates on the destruction of mithraea and, in particular, of images of the god sacrificing the sacred bull and of the massive images in some of the great temples of Egypt, and even beyond the Roman frontier. He is also at pains to defend himself against criticisms made, by R.L. Gordon, of his earlier work, while disagreeing with R. Turcan, who proposed that Christianity was successful in the Rhineland as early as the first half of the third century through its ability to offer a better understanding of reality than did the pagan cults. These concerns, however, sometimes make for lengthy arguments over details which tend to distract from the author's main thesis.

The early chapters concentrate on the fate of Mithraic shrines in the west. Among the Roman settlements, whether in the Agri Decumates, abandoned c. 260, or along the Rhine frontier, the same phenomena could be observed. Figures of the god and his worship have been carefully and systematically destroyed. Even fragments of statues have been pulverised. A statue of Mercury from the mithraeum at Dieburg had been hacked into 23 pieces. In Italy, the same process could be observed in the mithraeum at Ostia while, at Carmona near Seville, a large statue of an elephant had been smashed up and thrown into a well 20m deep. While barbarians could be suspected of carrying away loot from temples, their systematic destruction points to Christians and sometimes to their monastic leaders.

Monuments in some of the great Egyptian temples suffered identical damage. Sauer comments on the huge undertaking needed to destroy the giant Hathor heads and other monuments at Dendara. It is a pity that, at this point, he extended his research to what to him was unfamiliar territory, beyond the Roman frontier, at Qasr lbrim. The 'second-fifth century coins' allegedly recovered from the floor of the Ta Harqa (?) temple were in fact discovered by the reviewer at the base of a plinth outside the west entrance of the temple, covered with a wafer-thin layer of mud, as if forming part of libations. The main series dated from 277 (an Alexandrian billon tetradrachm of Probus) to imitation 3AE of the House of Theodosius. Moreover, bricks from the temple could not have been used in the construction of the cathedral, which was built almost exclusively of great blocks taken from the Ptolemaic temple, of which the podium, incorporated in the later fortifications of the site, formed the only surviving part.

Reasons for the progressive retreat of paganism in the Greco-Roman world remain obscure. The author discusses 'a world waiting for Christianity?'. He is certainly correct in arguing that Mithraism was among the last resisters to Christianity, pointing to evidence for its comparative prosperity, including many small coin offerings from the poor, as late as the reign of Theodosius I and even beyond. From the time of Justin Martyr (c. 150), it had been regarded as a most hated rival of Christianity (I Apol. 66), a prime example of demonic imitation of the faith, and hence the fanaticism with which its monuments were attacked.

Otherwise, Sauer is inclined to place the decisive advance of Christianity later than much of the evidence suggests. The Great Persecution (303-12) failed because, by then, Christianity was too strong both in town and countryside. Examples from some of the Mediterranean provinces may be quoted. Thus, Denis Roques (1987: 319) has shown that no priests of Apollo can be identified after 285-8. In North Africa, the last annual visit of the magistri of Aquae Thibilitanae to their grotto of Bacax was dated to 284 (Alquier 1929: 133), and the last known dated dedication to Saturn in Numidia was in 272 (Frend 1952: 84). At the same time, Coptic peasants in the Thebaid had turned with the enthusiasm of martyrs to Christianity by the time Maximin attempted to suppress them in 311 (Eusebius Hist. Eccl. viii.9.). On the other hand, Sauer is correct in placing the high point in the prosperity of Romano-Celtic temples in Britain as the Constantinian era or even later. The progressive Christianisation of the empire challenges further research.

The author ends on a sombre note, reminding his readers how the world watched in disbelief as explosives laid by Al-Qaeda and the Taliban reduced the great Buddha statues at Bamijan to powder. Fanaticism had returned. Where would it end, he asks. Sauer writes, therefore, with a sense of mission. His well illustrated descriptions of the remains of mutilated statues sound a warning note. Where he is writing as an archaeologist from his first-hand experiences he is powerfully convincing. Where he strays beyond his brief he is less so. He would have benefited from the essays in L'intolleranza (Beatrice 1990) for useful combinations of archaeological and literary evidence relevant to his theme. But with all said and done, this is an important book, a valuable contribution towards understanding the springs of early Christian fanaticism on its road to domination in the West.

References:

- ALQUIER, J. & P. 1929. Le Chettaba et les grottes à inscriptions latines du Chettaba et du Taya. Constantine: Paulette.

- BEATRICE, P.F. (ed.). 1990. L' intolleranza cristiana nei confronti dei Pagani.

Bologna: Dehoniane.

- FREND, W.H.C. 1952. The Donatist Church: a movement of protest in Roman North

Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ROQUES, D. 1987. Synésios de Cyrène et la Cyrénäique du Bas-Empire. Paris: CNRS.

Translated by M. Carver & M. Hummler.

|