DOMINIQUE BONNISSENT (ed.). Les gisements précolombiens de la Baie Orientale. Campements du Mésoindien et du Néoindien sur l'île de Saint-Martin (Petites Antilles) (Documents d'archéologie française 107). 245 pages, 152 b&w illustrations, 27 tables. 2013. Paris: Maison des sciences de l'homme; 978-2-7351-1124-4 paperback €46.

Review by Corinne Hofman

Caribbean Research Group, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, the Netherlands

(Email: c.l.hofman@arch.leidenuniv.nl)

This book by Dominique Bonnissent and colleagues demonstrates the possibilities and challenges of understanding the first human occupation of the insular Caribbean and the process of 'neolithisation' based on fieldwork at two very well preserved pre-Columbian sites (of the Archaic and Ceramic Ages) in Baie Orientale on the French side of St Martin in the Lesser Antilles.

Our understanding of the Archaic Age (referred to as 'Mesoindian' in this volume) and its transformation into the Ceramic Age ('Neoindian') is still hindered by several intricacies. As in many parts of the world, the process of 'neolithisation' is currently contested in the Caribbean, as has been shown by various recent works. Traditional ideas are currently being questioned: the adoption of a typical set of 'Neolithic' elements involving unilinear and unidirectional population movement; diffusion versus local development; sudden economic, demographic, socio-political and cultural change; sedentary lifeways; plant and animal domestication; and changes in subsistence. Hitherto-held notions about the onset of village life and its subsequent structural development throughout the Antillean pre-Columbian era no longer seem satisfactory based on current archaeological knowledge.

As recent research has attested, the archaeological record reflects a diversity of human activity resulting from complex fissions and fusions and mixtures of traditions, early forms of sedentism, pottery production and plant domestication from the Archaic Age onwards. During this period, it is suggested that the northern Lesser Antilles were visited from the surrounding regions skirting the Caribbean Sea and sparsely populated by communities who occasionally banded together in times of hardship, exchanging goods, services and knowledge, and engaging in ceremonies and rituals vital to the maintenance of population fitness. The data suggest that the islanders followed an annual mobility cycle that took advantage of seasonal biotic resources across the archipelago in areas that were targeted for non-subsistence activities: a form of archipelagic resource procurement and mobility. Communities possibly relied upon seasonality markers such as animal cycles, the succession of wet and dry periods, hurricanes, the navigability of the open sea and changing celestial configurations to structure their activities through time and across space. The establishment of networks in which the acquisition and exploitation of Long Island (Antigua) flint played a pivotal role probably functioned to maintain social relationships with nearby and distant communities. These extensive networks of human mobility and exchange of goods and ideas initiated during the Archaic Age, based on kinship, marriage, competition and other forms of reciprocity, amalgamated over time into what we know today as the Huecoid, Saladoid, Troumassoid and Ostionoid '(sub)series'—and peoples—of the Caribbean Ceramic Age.

St Martin is one of the best-studied islands in the Lesser Antilles, thanks to the implementation of the Valetta Treaty and subsequent work by the Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP). This book represents the first major preventive (or rescue) archaeology operation in the French Caribbean Islands related to the pre-Columbian period. The meticulous excavation methods and techniques are to be applauded and are clearly reflected in this very well-illustrated and accessible report. The description of the rigorous laboratory analyses of material culture and subsistence remains makes this volume a comprehensive contribution to the pre-Columbian archaeology of the Caribbean and to the current state of knowledge as sketched above.

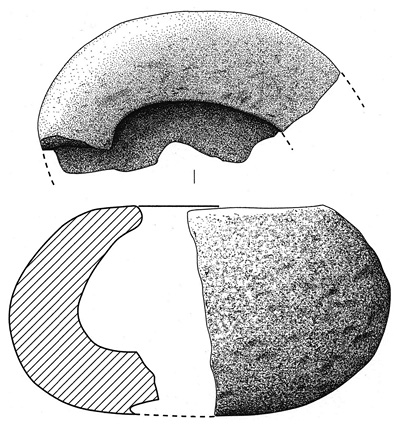

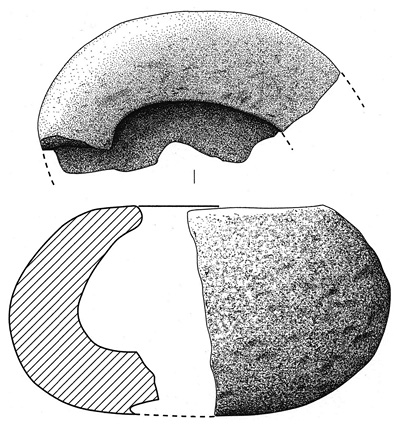

The book is divided into four chapters written in French, each preceded by extensive English and Spanish summaries, making it widely accessible for the international community of Caribbean scholars. The illustrations are highly informative and of excellent quality. The list of references, however, is far from exhaustive, and the book would have benefited greatly from a more extensive integration of the results into existing regional and macro-regional frameworks.

Following the solid presentation of environmental and chronological frameworks in Chapter 1, the second chapter deals with an Archaic Age campsite (800 BC–AD 100), where subsistence activities were associated with shell, stone and coral tool manufacture. A shell blade production workshop, caches and a specific lithic tool assemblage are interpreted as signs of proto-agriculture and pre-sedentarisation. These interpretations contribute to existing macro- and microbotanical studies and use-wear analyses from contemporary assemblages, which have repeatedly indicated the presence of early plant management and sedentism throughout the region during this period.

Chapter 3 includes the results from the Ceramic Age site (AD 740–960) represented by a simple midden characterised by Mamoran Troumassoid (Mill Reef style) artefacts and interpreted as a specialised satellite camp of a nearby village, corresponding to a territorial settlement pattern characteristic of the period on this and neighbouring islands.

The final chapter attempts to integrate the results into a regional perspective in which cycles of abandonment and reoccupation of the same locales for specialised exploitation of resources and activities throughout the northern Lesser Antilles during the Archaic Age gradually integrate and transform into more permanent settlements with satellite camps during the subsequent Ceramic Age. The early campsites and the toolkit at Baie Orientale perfectly fit this picture. As for the radical changes observed in later settlement patterns and material culture expressions in the area between the Early Ceramic (Saladoid) and Late Ceramic Age (post-Saladoid, Mamoran Troumassoid), the contributors confidently argue that a major impetus, alongside sociocultural factors, may have been the sudden change in climatic conditions from a wet to a dry period, corresponding to the Terminal Classic Droughts (TCD) and collapse of the Maya in the Yucatán region. The inclusion of the recent and prominent work of a number of Caribbean scholars on the reorientation of social networks as a result of the many socio-political, cultural and environmental constraints during this period would have been highly advantageous and greatly benefited these interpretations.

The real strength of this volume lies in the meticulous description of the thorough analyses of the two sites from Baie Orientale and their rich materials. It is to be hoped that the significance of this work will be developed and made more widely available through follow-up articles in which the results are more thoroughly incorporated into a state-of-the-art pan-Caribbean perspective and made to contribute to the current debates of scholars from the Caribbean region and beyond.