FELIX MULLER. Art of the Celts: 700 BC to AD 700. 2009, 304 pages, 9.5 x 11, 450 illustrations. ISBN-13: 978-90-6153-864-6. Hardback £45

FELIX MULLER. Art of the Celts: 700 BC to AD 700. 2009, 304 pages, 9.5 x 11, 450 illustrations. ISBN-13: 978-90-6153-864-6. Hardback £45

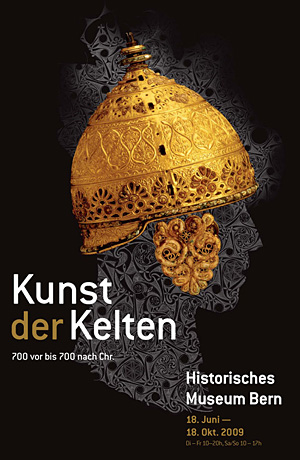

This exhibition certainly made its mark. Stepping out of the station, after a 5 a.m. start to a five hour journey, into the centre of Bern, my location was soon confirmed; every tram seemed to sport not only the coat of arms of Kanton Bern — a black bear — but the striking exhibition logo, a profile head comprising the gold covered helmet from Agris (Charente) (c. 350 BC) and the complex engraved design on one of the c. AD 700 Donore, Co. Meath, tinned bronze discs (Figure 1); though the Donore disc appears at several points in the exhibition and as end-papers to the book, it is unfortunate that it was not possible to include the actual piece in the display.

'Kunst der Kelten 700 vor bis 700 nach Chr.' ('Art of the Celts, 700 BC to AD 700'), staged at the Historisches Museum in Bern from 18 June to18 October 2009, is a worthy successor to some half-dozen major projects on similar themes presented over the past 25 years, adding to the seemingly inexhaustible list of exhibitions dealing with early Celtic art. A joint project with the Landesmuseum Württemberg in Stuttgart, it was conceived by Felix Müller, of the Historisches Museum and Honorary Professor at Bern University, in collaboration with his Stuttgart counterpart, Thomas Hoppe. Müller, whose doctoral thesis is one of a handful of modern in-depth studies of Iron Age art to appear in print (in 1989), has also revisited the emblematic La Tène cemetery of Münsingen-Rain near Bern (Müller 1998), discovered in 1906 and a key site for the relative chronology of Iron Age Europe. He and colleagues have recently demonstrated how it was the last resting-place of an inter-related high ranking group (Müller et al. 2008), so it is natural that finds from the cemetery should play an important if necessarily small-scale role in Bern again in 2009. Müller is also the main author of the text of the publication accompanying the exhibition (Müller 2009; full details in the references here) chiefly assisted by Martin Guggisberg of Basel University's Institut für Klassische Archäologie.

On the station bookstalls, and seemingly unaware that for some the concept of a Celtic Europe has no universal validity, a special edition of L'archéologue 103 (2009) vied for my Swiss francs with Damals 7 (2009) devoted to 'Kelten in Europa'. In Bern there has been a whole series of cultural events associated with 'Kunst der Kelten'. I am particularly sorry to have missed two performances in Bern's splendid Statdttheater of Vincent d'Indy's 'Fervaal', a product of the nineteenth-century Celtic revival based on the novel 'Axel' by Esaias Tegnér and first performed in Brussels in 1897. But there were compensations.

Making for the exhibition I entered the museum precinct under a reconstruction of the Gournay-sur-Aronde sanctuary gate, just as was on display at Lyon in 2006-7 (Goudineau 2006). Just to the right, Markus Binggeli, master metalsmith and specialist in reproducing archaeological material and Anna Kienholz from the Pädagogische Hochschule were finishing a full size replica of an extraordinary bronze couch. The original comes from the late Hallstatt chieftain's grave of Hochdorf and has obvious links with the 'situla art' of the Atestine region and what is now Slovenia (Frey 1989). Using nothing but original materials, copies of prehistoric tools and what is known of contemporary casting techniques the result was a tribute to modern craftsmanship. The 'Biedermeier couch' with its eight 'trick cyclists', naked women with coral-studded bodies, upraised arms supporting the main weight of the couch and feet attached to small spoked wheels is hardly less of a museum show-stopper than the original.

The main exhibition area within the museum's new annexe was divided into eight sections, each one supported by trilingual texts — German, French and English — and a range of film clips and computer graphics. Indeed the combined effects of artefacts, text and images achieved a near-perfect balance. From 'Before the Celts' through 'Impulses from the South' to 'In the shadow of Rome' and ending with the 'Late northern flourishing', this is a great deal more than an exhibition devoted to the fine and applied arts. Taken as a whole the texts provide the visitor with a very full overview of Iron Age Europe and the complexities raised by its study. All the more the pity, then, that there was no separate hand-list or brochure in addition to the hardback volume which is very much intended as a 'stand alone' book.

Both book and exhibition begin at the beginning, the former with a chapter entitled 'Who were the Celts? What is art?' and the latter opens with a section concerned with 'Before the Celts'. Throughout the term 'craft' is used as often as 'art' and as much space is devoted to techniques as to style. Although Müller and his collaborators do not explicitly state it, the terms 'Celt' and 'Celtic' are used as convenient shorthand while making it clear that:

'it is highly unlikely, based on the sources available, that Celts ever possessed an all-embracing identity. In this they shared the fate of other barbarian peoples that the more firmly established Greek and Roman communities came into contact with. It follows that "Celtic art" should also be viewed in a wider sense as a craft culture with stylistic idiosyncrasies that emerged and were developed on the north-western frontiers of the ancient world. ' (Müller 2009: 49).

This seems to me to be taking an eminently sensible middle way and one which argument for an early (i.e. prehistoric) use of the word 'Celt' would seem to support (McCone 2008).

The Bern exhibition contains a judicious balance of some old favourites and much less familiar finds. Questions of selection for inclusion or exclusion often bedevil major exhibitions which inevitably remain the triumph of compromise. The significant role played by the Stuttgart Landesmuseum is clear and a whole section is devoted to the Hochdorf princely burial centred around a scaled down replica of the burial itself. Not only Hochdorf but the inclusion of finds from the Kleinaspergle early La Tène grave group, both with attendant imports, offer a perfect case-study for the cultural interaction which typifies the early stage of the development of Celtic art. The great silver torc from Trichtingen forms another talking point; it is displayed next to another much debated and even more frequently illustrated object, the c. second century BC masterpiece that is the silver and gilt Gundestrup cauldron. As so frequently — and understandably — the latter was on this occasion represented by a copy. So too was the early La Tène stone knight from the Glauberg displayed together with the —original this time — gold torc from the first warrior grave of Barrow 1, echoing the form of that carved onto the statue (Figure 2). Amongst other earlier key pieces seen in the (restored) original was the figure from Holzgerlingen in Baden-Württemberg, another loan from Stuttgart, while from the Národní Muzeum in Prague there was a real coup: the original of the stone head from outside the rectangular closure of Mšecké Žehrovice. Almost as much a visual cliché as the Gundestrup cauldron the head was, as with other examples, tellingly contrasted with contemporary Classical sculpture — the Venus of Milo and the Prima Porta Augustus displayed like some ghostly cultural cousins.

Oher less well-known pieces included the now cleaned Horovicky phalera(e) from the nineteenth-century excavation of an early La Tène cart or chariot burial in Bohemia. With a double circle of 'leaf crown' heads, these echo the heads on the Holzgerlingen and Glauberg statues while the discovery in Glauberg grave 1 of a detachable 'leaf crown' framework irresistibly makes one think of children's parties rather than some sign of high if not indeed divine status as it surely is. Also recently cleaned — I fear somewhat over-cleaned — are the mounts for another and somewhat later chariot burial found in a local tholos tomb, Maltepe near Mezek in southern Bulgaria (Figure 3). Here are some of the finest examples of what I named many years ago the 'Disney style' dateable to the early third-century BC historical migrations of Celtic tribes in the Balkans and further afield. Of the same period and in the same style is the assemblage of mounts from Malomerice to the north of Brno (Czech Republic). These mounts, found in 1941 but unfortunately not precisely located within a large early La Tène flat cemetery, are best reconstructed as fittings for a spouted wooden flagon. The Bern exhibition offered a fine opportunity to compare chief examples of a style which also includes pieces from as far afield as Jutland and Sardinia and whose distributions are the object of several conflicting hypotheses.

Amongst later pieces in the exhibition are the superb individualistic painted ceramics from the region of Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dôme, France) dated to no later than the second century BC. Here the elongated quadrupeds once more recall the modern cartoonist's art, this time 'Fantasia' rather than Mickey Mouse. Other unique pieces are the more or less contemporary remains of some seven war-horns from the sanctuary site of Tintignac about half-way between Agris and Clermont-Ferrand. The bell of each horn, the 'carnyx' of later Greek writers, is decorated with strange beasts one of which had pride of place in the Bern exhibition. Strangely it appears in the book only as a spot on a generalised map of sites (see Maniquet 2008; 2009).

From a new find to one made in 1895 in Italy, the helmet from a double burial in a vaulted tomb at Canosa di Puglia. Many of the finds were dispersed soon after their discovery so that this is probably the first time since their discovery that the Celtic helmet — loaned from Berlin's Antikensammlung — has been reunited with the cuirass now located in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. Who was buried at Canosa is also a complex question; a Celtic mercenary is one possibility or more likely the helmet with its later embellishment was a trophy of a local Apulian knight (Olivier 1968).

Every exhibition should have a puzzle piece and for me the Bern puzzle is an unprovenanced shield decorated with what has been identified as an African gazelle. This originally found its way onto the antiques market and represents another loan from Stuttgart. Made of sheet bronze for a wooden backing, the oval shield with its central spina is in the first instance a typical Italic or Hellenistic form which seems to have been taken up north of the Alps. However, to claim a direct relationship with insular Iron Age shields as suggested by Martyn Jope seems highly unlikely (see Jope 1978: 30 & note 16; 2000: especially p. 60 and plate 61; Kunzl 2003). This is not to deny the influence of the Classical world as is to be seen in yet another prized item in the Stuttgart collection and one of the rare example of wood carving in the later La Tène period: a pair of goats, fragments of a group found in a deep well shaft in the square enclosure at Fellbach-Schmiden (Baden-Württemberg); recently the carving from oak planks has been dated by dendrochronology to 128 BC.

Space — and, I admit, personal bias — precludes much comment here on the later material in the exhibition which demonstrates the many ways in which Celtic style and Celtic cult survived well into the first millennium AD. One cannot fail to note the well-known bear-goddess bronze figurine from Muri near Bern dated to c. AD 200 which certainly offers evidence of the survival of a pre-Roman cult. Of much the same date are the openwork bronze sheath mounts produced by the master smith Gemellianus who worked at Aquae Helveticae (modern Baden in Switzerland); his handiwork with an almost totally Celtic stylistic repertoire was widely exported in Switzerland and southern Germany with one piece making its way to Morocco. A similar grafting of indigenous style onto provincial forms can be seen in Roman Britain in a range of complex enamel decorated vessels.

Inevitably not everything about 'Kunst der Kelten', either exhibition or book, is perfect. The absence of scales on the useful distribution maps is a small blemish. Perceived errors of fact as opposed to opinion — as in the cited history of the Basse-Yutz find or, more debateable, ascribing the Canosa helmet to the Waldalgesheim or 'Vegetal' style rather than to a group Otto-Herman Frey (1955) placed in an immediately preceding phase — are minor. The problems of displaying intricate detail are always difficult to resolve; here it affected the display of early La Tène miniature masterpieces including the rare brooch in human form from grave 74 at Manetín-Hrádek (Bohemia), and a uniquely shaped double brooch from Heubach-Rosenstein (Baden-Württenberg), no less than a Celtic Laocoön (Binding 1993: Kat. Nr. 68; Unruh 1994: 36 & Taf. 12). More fundamental has been the decision of the exhibition organisers not to publish even the simplest of case lists. In their place in the book after the main texts — which follow more or less the sequence of subjects covered by the exhibition — there is a 'catalogue' of some 40 selected objects ranging from Hallstatt C pottery and metalwork (700-600 BC) to the St Gall gospel book of c. AD 750. This 'musée imaginaire' includes objects which — like the Donore discs and the Basse-Yutz flagons — for one reason or another were not available for loan, the major lacunae being that nothing from either the British Museum or the National Museum of Ireland could be exhibited. For Britain the gap has been filled by loans from the National Museums Scotland. Again, one might have wished for more from Central and Eastern Europe such as the so-called 'false filigree' armrings and brooches first identified as an eastern, possibly Hellenistic influenced style by Miklós Szabó (see most recently Szabó 2009).

To return to the book — produced in German, French and English editions — it is itself a work of art displaying printing and design of the highest standard. Praise is also due to the translator of the English edition, Sandy Hämmerle, who, like all the best of such usually ignored wordsmiths, has produced a limpid text. I have no hesitation in recommending 'Art of the Celts' as a must-have to set beside those previously recommended in these pages (Megaw & Megaw 1992; Megaw 2007). Not surprising, then, that the Museum sold nearly 5000 copies even though this represents less than 15 per cent of the visitors recorded.

There can be no doubt as to the success of 'Kunst der Kelten'. With more than 71 000 visitors this represents twice the number of those attending recent comparable exhibitions in the Low Countries. Those who missed the Bern show can look forward to the exhibition re-opening in Stuttgart on 15 September 2012. Indeed Celtosceptics may have their work cut out. From the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento, northern Italy, comes news of an exhibition scheduled for 2011 covering contacts, exchange and trade between the Mediterranean world and Central Europe from earliest times to the rise of Rome. That of course will include the art of the Celts.

My thanks are due first and foremost to Felix Müller for his generous welcome and to his colleague Jolanda Studer, responsible for picture research and much else, and for answering innumerable emails.