GAVIN LUCAS (ed.) with numerous contributors. Hofstadir: excavations of a Viking Age feasting hall in north-eastern Iceland (Institute of Archaeology Reykjavik Monograph 1). xxiv+440 pages, 226 illustrations, 150 tables. 2009. Reykjavik: Fornleifastofnun Íslands (Institute of Archaeology, Iceland); 978-9979-9946-0-2 paperback ISK5990, £30, $48 & €35 + p&p.

Review by Søren M. Sindbæk

Department of Archaeology, University of York, UK

(Email: soren.sindbaek@york.ac.uk)

Early medieval housing is rarely studied in better detail than in the Scandinavian settler communities of the North Atlantic Ocean. When transferred into the sub-arctic climate, traditional timber buildings were clad in thick, insulating turf walls, which have secured the survival of an amazing archaeological record. For a long time this record saw notably little investigation. In Iceland in particular, it seemed difficult to justify traditional excavation projects in a country where medieval texts narrate history farm by farm back to the time of the initial settlement. Since the 1990s, however, Icelandic archaeology has seized the potential of historical archaeology, revealing developments of society and environment which were unknown or inconvenient to saga writers. Hofstaðir in north-eastern Iceland has been at the hub of this transition.

This book presents ten seasons of fieldwork in a single house and its outbuildings, in use in the period c. AD 940–1070. First investigated in the early twentieth century as the supposed site of a pagan temple, Hofstaðir was re-visited in 1991–2002. The site was quickly re-identified as a chieftain's residence, albeit still associated with pagan rituals. It was subjected to a multi-faceted programme of detailed excavation, palaeoenvironmental studies and bioarchaeology.

The report is introduced by a study of the palaeoenvironment of Mývatnssveit, the region around Hofstaðir. Written by Ian Lawson, with several contributors, it presents impressive detail derived from palynology, soil profiles and thin sections as well as from archaeofaunal data. The results are further backed by an environmental simulation by Ian Simpson. These studies offer important qualifications to the picture of human-induced environmental damage popularised by Jared Diamond and others in recent years: Icelandic settlers quickly became aware of the impact their traditional farming practices had on the sensitive, sub-arctic landscape, and they reacted in flexible, knowledgeable and mostly efficient ways. Their long-term effect on the landscape was as much a case of improvement as of degradation. Both studies conclude (pp. 53–4, 370) that Icelandic farmers settled on a regime which proved viable for over a millennium, as witnessed by the still-existing farm at Hofstaðir.

The excavations of the hall and its associated buildings is presented and analysed by Gavin Lucas with separate chapters on the archaeofauna by Thomas McGovern, the artefactual material by Colleen Batey (all with numerous further contributors) and plant remains by Garðar Guðmundson. McGovern delivers a surprising vindication of the association of the building with pagan ritual. A group of cattle skulls with abnormal butchering marks indicates that the animals were killed by a blow between the eyes and apparently simultaneously decapitated by a powerful slash with a sword or axe from the side: an immensely impractical technique, but capable of producing a spectacular blood fountain as the animal's heart would still be beating (p. 249). Afterwards the skulls seem to have been displayed in the open, as they showed clear signs of weathering.

Lucas presents a subtle and detailed analysis of the building remains, their sequence, spatial organisation and use. His interpretation is greatly enriched by the evidence from dumps and floor deposits, which have survived surprisingly well despite earlier excavations. The architecture of the buildings is treated more superficially, and with a rather cursory look at Scandinavian parallels. Some aspects call for comments from the point of view of that Scandinavian corpus of buildings.

A set of beam slots apparently marks partitions in the side aisles of the main hall. Lucas speculates that these indicate individual sleeping berths or cubicles, presumed 'to accommodate non-kin' (pp. 387, 394). This interpretation stands out starkly against the grand, open rooms, which appears to be the very point of Scandinavian hall buildings, as witnessed by the architectural innovations brought about to achieve them. As Lucas notes (p. 375) no such partitions are known from other comparable buildings. When partition walls occur in Scandinavia, these consist of a line of vertical posts, which presumably supported a cladding of daub or horizontal planking. One wonders if the horizontal beam slots observed at Hofstaðir are simply joists, designed to carry the floor planking of the side-aisle platforms?

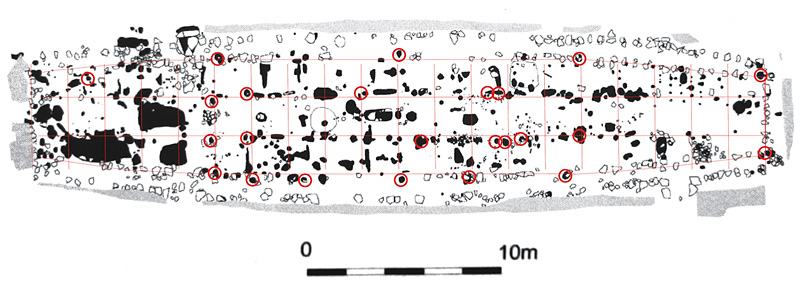

As for the hall building's structure, Lucas sees little patterning in the rows of postholes, which divide the hall into three aisles. Many, he claims, were 'obviously later insertions [...] though it is impossible to phase the posts as a group' (p. 70). This is perhaps too pessimistic a view. While most holes are shallow, and may relate to the platforms, a small number of deep-set features, >35cm deep, seem to be aligned on a regular grid (see figure, after Lucas with additions: rings indicate deep set [>35cm deep] posts). This divides the length of the building into four sections of equal length, each further divided, apparently on a unit of c. 1.85m. This is a measure, corresponding to a fathom (6 feet), often seen in Scandinavian buildings of this time. A great deal of architectural planning evidently remains to be revealed in this building.

This symmetry also speaks against a further suggestion, based on various hints (p. 113), that the hall was originally planned as a shorter building, and only reached its full length as a consequence of a substantial enlargement towards the end of the tenth century. Such a change would assume either that the early building was planned to a skewed outline, or that substantial adjustments were made to the wall-line in the central part of the building, none of which seems likely on closer observation.

These and other elements emphasise how closely this Icelandic site is connected to the wider world, and what potential the material presented in this book has to offer. Hofstaðir sets a bench-mark for Icelandic archaeology — it is, appropriately, volume 1 in a series published by the Icelandic Institute of Archaeology. As a state-of-the-art excavation, processed and published in full detail, it will become a standard reference for the study of Viking Age society, early medieval housing and settlement in environmentally sensitive landscapes.