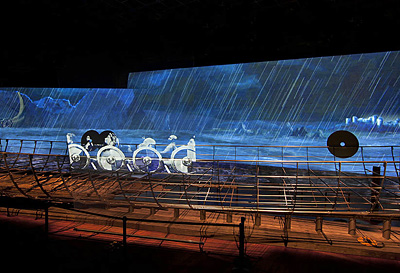

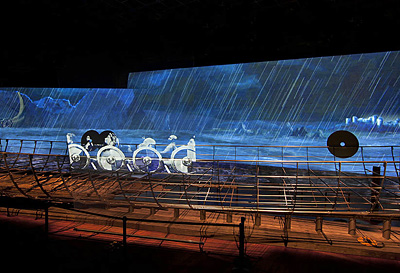

Figure 1. The Viking ship 'Aegir' with the animated video playing behind. Photo: The National Museum of Denmark.

Click to enlarge.

Review by Jes Wienberg

Department for Archaeology and Ancient History, Lund University, Box 117, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden

(Email: Jes.Wienberg@ark.lu.se)

The temporary exhibition 'Viking' is currently on show at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen from 22 June–17 November 2013, and will be on display in London from March–June 2014 and Berlin from September 2014–January 2015. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue, titled Viking , edited by Gareth Williams, Peter Pentz & Matthias Wemhoff.

Vikings are here again. Even before the Swedish archaeologist Oscar Montelius and the Danish archaeologist J.J.A. Worsaae established the term 'Viking Age' in the 1870s, the era and its inhabitants had a firm position in the perceptions of both the past and the present. The Viking and the Viking Age have filled the need for Nordic glory in the past, when the present was only too grey. Whereas Viking in its contemporary context meant a pirate or piracy, it has now assumed a wider meaning. In the Viking and the Viking Age every present might find what it is looking for—expansion, treasures, boldness, honour, farms, agriculture, handicraft, design, kings, noblemen, thralls or cooking. Vikings are excellent both for internal self-identification and for external relations. Vikings as a theme for university courses, re-enactments, tourism, books, movies and exhibitions are alluring on a global scale.

Large exhibitions on Vikings have occurred at regular intervals. The last large exhibition was 'From Viking to Crusader', which travelled in 1992–93 from Paris to Berlin and Copenhagen. Now the National Museum of Denmark, in cooperation with the British Museum in London and the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Berlin, has created a new exhibition, titled 'Viking'. The exhibition starts in Copenhagen, but is to be shown also in London (from 6 March to 22 June 2014) and Berlin (from 10 September 2014 to 31 January 2015).

The dominating focal point of the exhibition both visually and metaphorically is the Viking ship. A large sail presides over the entrance hall of the museum and the exhibition itself is organised around the impressive frame of the longest known Viking ship, with the original timber remains inside exhibited for the first time ever (Figure 1). The ship is known as 'Aegir' or the wreck Roskilde 6 and was once 37m long. It was built c. 1025 at the Oslo Fjord in Norway and excavated in the harbour of Roskilde in Denmark in 1996–97. In the background, on a screen as long as the ship, the visitor cannot fail both to see and hear the ship on its voyage in an animated movie.

Around the ship the exhibition is divided into five themes: the Viking World, Raids & War, Power & Glory, Belief & Ritual and Formed by the Ship. Here, many spectacular finds (and a few replicas) from 12 countries gather in showcases together with pictures, listening posts and game stations (Figure 2).

'Viking' is a multi-media exhibition. It deliberately appeals to the senses. You might follow a guided tour or stroll on your own through the exhibition listening to the information downloaded to your smartphone. In the rather dark room attention is drawn to the impressive ship and the on-going movie with the sound of waves, and to the light of the showcases with their clever touch screens, where the language can be toggled between Danish and English and where pictures can be enlarged. It is drawn to shifting colourful photos from different parts of the Viking world; to the listening posts, where you might hear a Viking; to the presence of an acting Viking, who helps you to dress as a wealthy warrior (used both by children and adults); and to the game stations, where you are encouraged to show your Viking father that you have the knowledge and the courage to be a real Viking in the computer game 'the First Raid', where the results can be shared on Facebook. At the exit, another touch screen allows you to write a runic text on an interactive runic stone. Thus the exhibition is a firework of both new knowledge and new possibilities of experience, which should appeal to all ages.

During the period of the exhibition the National Museum also had a Viking market and was visited by the 'Sea Stallion from Glendalough', the largest reconstructed sailing Viking ship. After a visit you could have a Viking meal. In addition, for the more patient reader there was a heavy and well-illustrated catalogue to carry home with 14 articles divided into the same themes as the exhibition and followed by an overview of the exhibited finds in the form of text (Williams et al. 2013).

The multi-media is not the message. The ship as a creator of a larger world is the message. The message of the exhibition is how the Nordic Viking was a bold traveller into the world, depending on the context either as a violent warrior or as a peaceful merchant—and also how the world with both people and things came to the North. As one might expect from any exhibition, 'Viking' is also a comment on the present, however implicit. One of the first showcases displays the self-evident presence of 'foreign' objects and people in the North, thus indirectly making a comment on the politically related question of immigration. Associations extend also to the mix of trade and military action we see abroad in relation to other countries in recent decades.

The Viking as a merchant and warrior is one choice among several possibilities for the study of international contacts, and for national and individual self-identification. As a critical comment I did not observe many possibilities for women or other social groups to be seen and heard. The focus is on the Viking as a male without an ordinary everyday life. Thus the movie ends with daddy returning home after his 'viking'. Women appear sparsely; for example, in a showcase with jewellery (Figure 3). Maybe I missed it, but I would have liked some explanation in the exhibition on why Vikings went abroad and why they stopped doing it. Why Viking and a Viking Age at all? Was it the technological innovation of the sail that created an era—and a mental transformation, Christianisation, which ended that era? Or did the Viking become a Crusader as in the previous exhibition? I would also have liked a theme in the exhibition on the use and maybe misuse of the Viking Age since the concept was established; it only now exists as an option for high school classes in the standard exhibition of Danish prehistory at the Museum.

Even though I would have liked to see a well-preserved Viking ship such as the Gokstad ship as the focus, to have seen a real Tating ware jug, the real double-head idol from Fischer-Island in Neubrandenburg and the real bell from the harbour of Haithabu, rather than replicas, and have listened to Icelandic as in the York Viking exhibition, not modern language, I still think that this exhibition has found a successful way of storytelling and mediating using the core museum material and the original finds, together with new multi-media and re-enactors. Picking the best from all worlds!

The new Viking exhibition is both informative and beautiful. After my first visit I will return to see it again with both my family and colleagues before it goes 'viking' in the world.