The colours of corn: John White’s Florida watercolours

John White, born in the 1540s and last heard of in 1593 in Ireland, is known for the five voyages to North America that he took part in between 1584 and 1590, mostly to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Virginia Colony, and for the 75 watercolours that now survive in the British Museum (Hulton & Quinn 1964; Hulton 1985; Sloan 2007).

The most noted of these watercolours were made on the 1585 expedition and portray the Algonquin people of what is now coastal North Carolina; others include fanciful notions of ancient Picts, based to some extent on his Amerindian observations, and of Baffin Island Inuit (although White did not necessarily accompany Frobisher there in 1576).

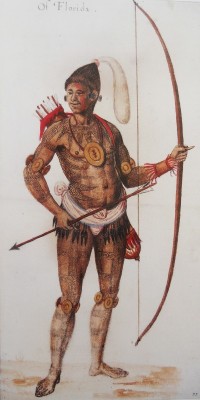

Two of the watercolours depict a Timuacan man and woman, from the St John’s River region of central Atlantic-coastal Florida (BM accessions Prints and Drawings, 1906, 0509. 1.22–23). They are labelled only ‘Of Florida’, without the detailed captions on his Virginia paintings, and are thought to be copies by White of now lost originals by the Huguenot Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues (1533–1588).

The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Available at: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7bee-a3d9-e040-e00a180... (accessed 22 July).

Le Moyne was in Florida in 1564–1565 and was then in London from 1581 until his death. What may be one of his original gouaches shows the commemorative pillar bearing the arms of Charles IX of France that Jean Ribault had raised in Florida in 1562, alongside the local chief’s son, Athore, greeting Le Moyne’s captain René Laudonnière on 27 June 1564, and with containers of local produce apparently as offerings in front of the pillar (Figure 1). The food offerings include gourds of (probably) beverage, baskets of fruits and vegetables and a tied bundle of maize cobs (Sloan 2007: fig. 77; engravings of Le Moyne’s drawings, including this one, were published by Theodore de Bry in 1591 in Frankfurt; De Bry had already published engravings of White’s drawings the previous year, see Hulton 1977, 1985).

White’s two putative copies from Le Moyne labelled ‘Of Florida’ are in the same style as his Virginia watercolours; the man (Figure 2) is heavily tattooed and wears a loincloth with many pendants, apparently of metal and possibly being brass aglets used in European costume of the period to link doublet and breeches (Martinón-Torres et al. 2007 show the adoption of these as jewellery in sixteenth-century Cuba). He also has flat elliptical metal ornaments on his arms and knees, and as a pectoral. These may also be of European manufacture, or perhaps indigenous trade goods from Colombia via the Antilles. If European, they would probably have been of brass; if Colombian, of gold or a copper-gold alloy such as tumbaga. While he resembles, in his armament and adornment, figures from De Bry’s engravings after Le Moyne’s lost originals, he does not replicate any of them; Sloan (2007: 134) notes the resemblance of his tattoos to Elizabethan strapwork, and this may indicate an ex post facto adaptation by either Le Moyne or White.

The woman is also tattooed in similar fashion from forehead to wrists and ankles (Figure 3), and wears two necklaces as well as fish bladders in her earlobes (Sloan 2007: 136 & plate 20); it is not clear whether she also has a labret through her lower lip. Her costume is striking, albeit impractical, in its brevity: long blue icicle-like points hang from a red-and-white band over one shoulder, beneath which she is naked. It implies ceremonial rather than everyday garb. Sloan (2007: 136) suggests it is made from Spanish moss, which grows commonly on trees in Florida and Carolina, although the red-and-white border would seem to be fabric. She again resembles, but does not duplicate, the figure of a chief’s wife in De Bry’s engravings: the most economical explanation might be that both the male and female figures were drawn from life by Le Moyne, and formed part of a scene not used by, or not in the hands of, De Bry. This matter, however, is tangential to my main point—the identification of objects held in the woman’s hands.

In her left hand (Figure 4) she holds a pottery bowl containing three fruit-like objects, now in a pale blue so faded that their identity is uncertain, although they are possibly pineapples. Her right hand holds out five cobs of maize, which are explicitly, although sketchily, shown as being red, black, white and (two) yellow in colour (Figure 5).

This is of considerable interest, as these are the four colours of the world directions in the cosmology of parts of Mesoamerica (southern Mexico and western Central America), notably the Maya civilisation. There, red (chak) signified the east and sunrise, black (ek) the west and sunset into night; white (sak) was the north and also upwards into the blinding light of the heavens, while yellow (k’an) was the south and the underworld. The path of the sun cycled through all four on its diurnal round. The cosmic centre and axis mundi were blue-green (yax).

On pages 26 and 27 of the Madrid Codex there is an almanac in which deities offer maize in these five colours: Gabrielle Vail (pers. comm. 2015; see also Vail & Hernández 2013) notes that

There is a set of almanacs on pages 24–28 of the Madrid Codex that refers to planting. Most commonly, Chaak [the Maya rain deity] is the one doing the planting, and the almanacs are pretty consistently divided into four or five frames, associated with the colour-directional aspects of Chaak. In the almanac in question [on Madrid 26d–27d], the hieroglyphic captions contain a verbal compound that remains unread [at B1, E1 and G1], and a reference to a particular colour of maize [yellow in frame 1, black in frame 2, white in frame 3, red in frame 4, and blue/green in frame 5]. This suggests a directional circuit beginning in the south, moving to the west, then to the north, the east, and finally the centre.

Eric Thompson (1934) discussed the Maya associations of these colours with the cardinal points, the four quarters of the world and the sky-bearer gods, which appear in hieroglyphic sources (the Dresden and Madrid Codices), in sources transcribed from Maya into European script (the Ritual of the Bacabs, the Chilam Balam of Chumayel), and in Diego de Landa’s ethnographic compilation, the Relación de las cosas de Yucatan (see also Tozzer 1941, especially pp. 137–38 and notes 635–38).

The use of four-coloured maize in what may, from the woman’s striking but abbreviated costume in White’s rendering, be a ceremonial action could hint at ideas transferred from Mesoamerica to Florida. Given the man’s elaborate metal ornaments, he may also be in ceremonial garb, and it is possible that we should associate the two copies of Le Moyne by John White with the ritual depicted on the putative Le Moyne original in New York or one much like it.

The bundle of maize shown by Le Moyne contains 10 white and 10 red cobs: the number 20 was of considerable significance in Mesoamerica, being the base for the vigesimal calendar and numeration system: the 260-day Aztec tonalpohualli cycle and Maya tzolkin (Sacred Round) were multiples of 20 named days with the numbers 1–13. The use of just red and white may matter: among a number of contemporary Maya cultures, east (red) and north (white) define the sunrise to sunset positions, thereby corresponding to the daytime and to the solar (male) realm, as opposed to the lunar (female) realm. Red and white are significant in several contact-period South-eastern United States cultures in terms of being linked to the dual system of peacetime chiefs (associated with white) and war chiefs (red) (Gabrielle Vail, pers. comm. 2015). The male cast of the ceremony depicted by Le Moyne in Figure 1, albeit with a background chorus of semi-naked women, may be relevant to the bicoloured maize bundle.

For the late pre-Hispanic Maya, however, the combination of sunrise (red) and zenith (white) colours is not important: in the Dresden Codex, north and south (white and yellow) have positive associations, while east and west (red and black) have negative associations. In the Madrid Codex (and in Landa), north (white) and west (black) years have the most negative prognostications. Generally, the south has extremely positive associations in both codices, as it is linked with the deity K’awil and sustenance. The two yellow cobs seem to suggest that the southern direction, perhaps because of its association with abundance, is being emphasised (Gabrielle Vail, pers. comm. 2015). Whether the use of precisely 20 bundled cobs in Le Moyne’s depiction is the result of Mesoamerican contact or just coincidence remains moot.

Maize is rare as a crop in Florida until after AD 1200, when it is found at, inter alia, the Browne Mound and Holy Spirit sites on the lower St John’s River (Hutchinson et al. 1998). These are mortuary sites, and the populations had a marine-oriented diet with little maize. Hutchinson et al. (1998) note increased maize usage after Spanish contact, suggesting that new routes of communication, perhaps including greater distance maritime ones, could have been a factor. Although maize was in use in upstate New York from the late first millennium BC onwards, having apparently spread north and east from the US South-west, it seems to have trickled southwards through Georgia into Florida much later on: it is possible, given the post-Contact date for expansion of maize use there, that this resulted from maritime rather than terrestrial exchanges, and that these ultimately may have been with Mexico. If so, why and how maize colour-symbolism came along with the comestible is intriguing, but perhaps unascertainable.

No proven links between the Maya area and Florida have yet been found (and most Florida archaeologists remain sceptical), although Bullen (1966) suggested that the standing stelae with associated offerings of the mid-first millennium AD at Crystal River on the Gulf Coast north of Tampa resulted from such contact, either direct or mediated through the Antilles. The apparent ritual use of maize on the St John’s River in the 1560s as recorded by Le Moyne may have been a response to the novelty of this crop as much as to its utility, and the striking parallels with four-colour symbolism are worthy of further study.

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 is used by courtesy of The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library; and Figures 2–5 by courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum. For detailed advice on the Madrid Codex and ethnohistoric data, I am grateful to Gabrielle Vail.

References

- BULLEN, R. 1966. Stelae at the Crystal River site, Florida. American Antiquity 31: 861–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2694459

- HULTON, P. (ed.). 1977. The work of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, a Huguenot artist in France, Florida, and England. London: British Museum Publications.

- HULTON, P. 1985. America 1585: the complete drawings of John White. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press.

- HULTON, P. & D. BEERS QUINN (ed.). 1964. The American drawings of John White. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press.

- HUTCHINSON, D., C. SPENCER LARSEN, M. SCHOENINGER & L. NORR. 1998. Regional variation in the pattern of maize adoption and use in Florida and Georgia. American Antiquity 63: 397–416. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2694627

- MARTINÓN-TORRES, M., R. VALCÁRCEL ROJAS, J. COOPER & T. REHREN. 2007. Metals, microanalysis and meaning: a study of metal objects excavated from the indigenous cemetery of El Chorro de Maíta, Cuba. Journal of Archaeological Science 34: 194–204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.04.013

- SLOAN, K. (ed.). 2007. A New World: England’s first view of America. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press & British Museum.

- THOMPSON, J.E.S. 1934. Sky bearers, colors and direction in Maya and Mexican religion (CIW Publication 436, Contribution 10). Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington

- TOZZER, A.M. (ed.). 1941. Landa’s relación de las cosas de Yucatan (Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University 18). Cambridge (MA): Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology.

- VAIL, G. & C. HERNÁNDEZ. 2013. The Maya Codices Database, Version 4.1. A website and database. Available at http://www.mayacodices.org/ (accessed 22 July 2015).

Author

* Author for correspondence.

- Norman Hammond*

McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3ER, UK, & Department of Archaeology, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston MA 02215-1406, USA (Email: ndch@bu.edu)

Cite this article

Cite this article