Recent excavations at a Megalithic jar site in Laos: site 1 revisited

Introduction

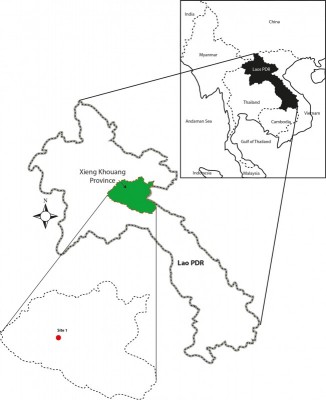

The megalithic stone jar sites of Laos remain one of Southeast Asia’s enduring archaeological mysteries (Figure 1). These sites were first brought to the attention of western scholars by Madeleine Colani (1935) who documented dozens of jar sites and conducted excavations in several locations. The sites, which are most commonly found on the summits of hills or on flat plains, comprise large stone jars, averaging 1–1.5m (with examples up to 3m) in height and 2m in diameter, clustered in groups across the landscape. Some of the larger sites have more than 300 stone jars. Most jars are carved from sandstone but some are fashioned from conglomerate, granite or breccia. Although the stone jars remain undated, it is probable that they were created during the Iron Age (c. 600 BC–AD 500) on the basis of associated material culture.

Since Colani’s creditable efforts, only limited research has been undertaken on these sites (Nitta 1996; Sayavongkhamdy & Bellwood 2000; Genovese 2012). Van Den Bergh undertook an extensive survey in 2007, expanding the number of known sites to 85 (Van Den Bergh pers. comm.).

The jar sites located in Xieng Khouang Province, Laos, are the focus of an Australian Research Council project entitled ‘Unravelling the Mystery of the Plain of Jars’, led by Dougald O’Reilly (Australian National University), Louise Shewan (Monash University) and Thonglith Luangkhoth (Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism). The project seeks to understand the function of the megalithic jars, to examine the geographic extent of the associated culture and to assess the role of the sites in the context of burgeoning inter-regional exchange networks of the period. These aims will be achieved through the application of a range of archaeological and analytical techniques.

The 2016 excavations

Three excavation units were established at site 1 (Figure 2), located around 5km from the city of Phonsavan, Xieng Khouang Province. An extensive inventory of jars, boulders and discs was undertaken, and the location of each geo-referenced. The morphology of each jar and the type of stone used has been recorded and every object photographed.

Unit 1

An excavation unit measuring 3 × 3m, with small extensions, was established within group 2 at site 1, based on the presence of numerous varied surface features, including large jars carved from sandstone and conglomerate, a sandstone disc and quartz-veined sandstone boulders. In the first 200mm of this unit a substantial number of sandstone chips (n = >100) were discovered, indicating the possible retouching of the large stone jars. This explanation is supported by the discovery of two hammerstones in the units, one adjacent to a stone jar.

Three mortuary contexts were uncovered in unit 1. Human remains were discovered resting atop four limestone boulders below a large sandstone disc. A second and third burial were discovered in association with worn limestone boulders. All the human remains were fragmentary; the secondary burials were comprised of teeth and pieces of long bone. Items of material culture recovered from unit 1 include iron fragments, three spindle whorls, a hammerstone, a whetstone, ceramic vessel sherds and a miniature ceramic vessel. Items of jewellery include a perforated stone pendant and two ceramic ear plugs, an agate bead (mortuary context two), a Indo-Pacific glass bead (mortuary context three) and two carnelian beads (one associated with each of mortuary contexts two and three).

Unit 2

A 2 × 2m unit was selected for excavation based on the results of a ground-penetrating radar survey, which indicated the presence of a significant sub-surface anomaly. The upper 200mm of this unit, similar to unit 1, contained a substantial quantity of sandstone chips, so dense in one part of the unit as to almost form a ‘pavement’.

The unit revealed a primary burial comprising the remains of two individuals: an adult skull and post-cranial remains, and skull fragments and the mandible of a child. The adult (Figure 3) was covered with a large, flat limestone slab, with the deceased’s face roughly aligned with a perforation through the slab. Material culture from the unit includes iron fragments, a single Indo-Pacific glass bead, a spindle whorl, a hammerstone, ceramic sherds and a miniature ceramic vessel similar to the one recovered from unit 1.

Unit 3

A 2 × 2m unit was selected for excavation to investigate the areas associated with a sandstone disc (750mm in diameter) with a central pommel on either side and a large, quartz-veined boulder.

The unit revealed two mortuary contexts and four potential jar burials (the contents are yet to be examined). Mortuary context four consisted of an isolated tooth fragment and a burial jar with incised decoration. The second mortuary context, number six, consisted of isolated human long bones and some teeth. Material culture from the unit includes a whetstone, iron fragments, ceramic sherds, a small bronze object associated with mortuary context six, and three reasonably intact burial jars (Figure 4), and a fourth burial jar in the north baulk positioned directly under a quartz-veined sandstone slab (Figure 5).

Summary

The recently concluded field season has established that the jar field was used for mortuary purposes, with evidence for primary and secondary burials and potentially buried inhumation jars. There is no evidence of any occupation at the site, and the period of activity appears, based on the distribution of debitage and artefacts, to have been chronologically limited, although a better understanding of dating should emerge when radiocarbon samples are processed. It is clear that a range of grave markers were used, including sandstone discs, limestone boulders and quartz-veined blocks. The research project will continue until 2019.

Acknowledgements

The project is funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project (grant DP150101164). Thanks to GBG Australia, MoICT staff, student volunteers from the National University of Laos, site 1 concession proprietors, and volunteers from Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland.

References

- COLANI, M. 1935. Mégalithes du Haut-Laos. Publications de l’école francaişe d’Extrême-Orient nos Les Éditions d’art et d’histoire: 25 & 26.

- GENOVESE, L. 2012. The plain of jars: mysterious and imperilled. Unpublished report. Available at: http://ghn.globalheritagefund.com/uploads/documents/document_2006.pdf (accessed 23 May 2016).

- NITTA, E. 1996. Comparative study on the jar burial traditions in Vietnam, Thailand and Laos. Bulletin of the Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Letters, Kagoshima University 43: 1–19.

- SAYAVONGKHAMDY, T. & P. BELLWOOD. 2000. Recent archaeological research in Laos. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 19: 101–10.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Louise Shewan*

Centre for Archaeology and Ancient History, Monash University, Clayton Victoria, 3800 Australia (Email: louise.shewan@monash.edu) - Dougald O’Reilly

School of Archaeology and Anthropology, The Australian National University, ACT 2601, Australia (Email: dougald.oreilly@anu.edu.au) - Thonglith Luangkhoth

Department of Heritage, Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism, Vientiane, Lao PDR (Email: thonglith_top@yahoo.com)

Cite this article

Cite this article